Written by SUSK Canada Summer Job Intern – Daniil Zhelezniak (Saint Mary’s University)

The Uniqueness and Importance of Pylyp Orlyk’s First Democratic Constitution

Globally, there are many versions of the origin of the first democratic state’s normative documents, and the American Constitution option is often preferred, with the majority of attention given to it. However, only a small proportion of people realize that it was Ukrainians who initiated the development of documents where the foundation was laid for the separation of branches of government and the rule of law. Moreover, this is especially striking in a detailed analysis of the events and the time epoch that accompanied it, which will be conducted in this article.

Historical Context

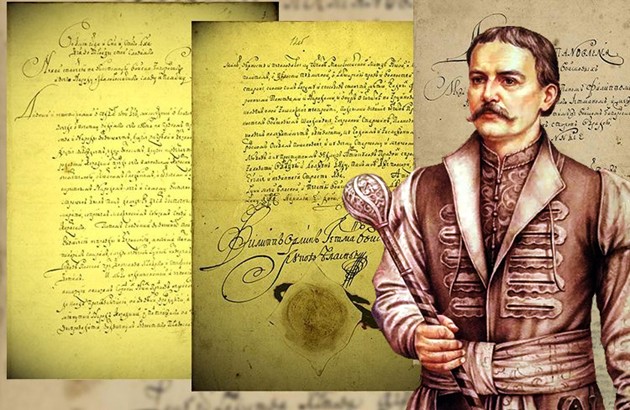

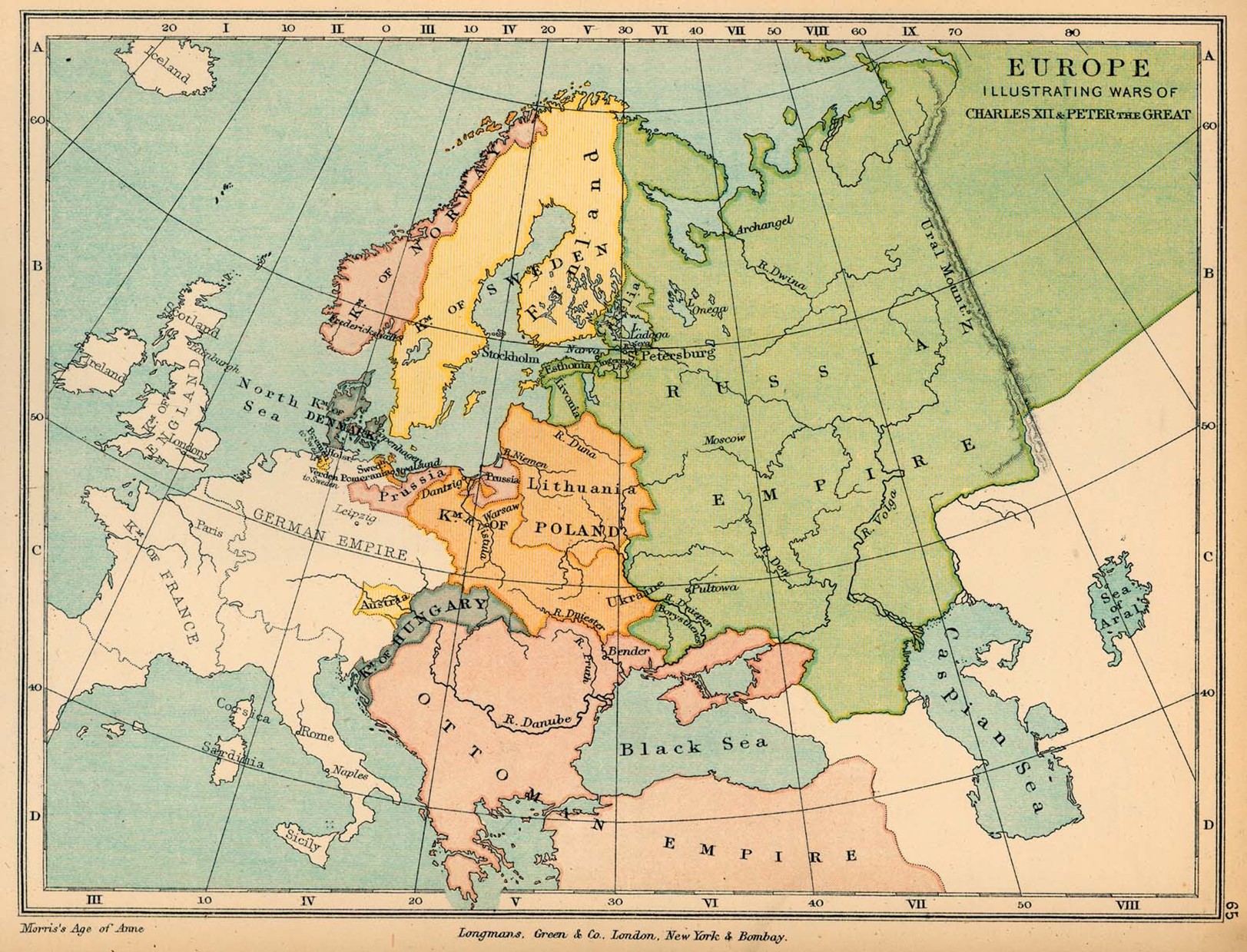

The published constitutional document, in 1710 by the Cossack Hetman of Ukraine in exile, Pylyp Orlyk, known as the Treaties and Resolutions of the Zaporizhian Host, better known as the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk, had rather extraordinary prerequisites. After the defeat in the Battle of Poltava (Great Northern War) of the Ukrainian commander-in-chief of the Cossack Hetmanate, Ivan Mazepa, who sided with Sweden against the Russian Tsar Peter 1 and the troops of Hetman Skoropadsky, in 1709, Mazepa fled and died in exile in Moldavia (Weiss, 2023). On April 5th, 1710, Pylyp Orlyk, a close associate of Mazepa, was elected as a Hetman of the Cossacks in exile in the city of Bendery (Moldavia) with the support of the Swedish King, which made him the political leader of the Ukrainian forces abroad (Vasylenko, 1958, p.1264). At the age of 38, Orlyk had a truly outstanding biography; he received an elite Jesuit education at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, was fluent in several languages, and had extensive experience in legal affairs, diplomacy, and public administration, serving as the General Chancellor of the Hetmanate (Subtelny, 1990). On the same day, as the inauguration, the constitution was published, reflecting the aspirations of the new leadership to reorganize the Cossack government and the desire to reach the hearts of Ukrainians in the uncontrolled territories. The context of the need for cooperation with Sweden, the military defeat and political exile strongly influenced the content of the Constitution: It was a manifesto for a sovereign Ukraine and against foreign domination (clearly aimed at achieving independence from Moscow and Poland) and a plan to prevent internal contradictions and tyranny from which many states suffered in the 18th century (Wilkerson, 2023). In other words, a difficult historical moment like the loss of Ukraine’s autonomy in favor of imperial Russia and the split of the Cossack army (after all, as mentioned above, another prominent leader of those years, Ivan Skoropadsky, supported Russia) became the engine of constitutional changes.

Democratic Features and Importance of 1710 Constitution

Despite the fact that the Orlyk Constitution was written back in the early 18th century, it contains surprisingly developed liberal features that significantly anticipate later constitutions, as the US Constitution was ratified only 78 years later, and the Canadian one only 150 years later (Vovk, 2010). One of its most notable attributes of the Ukrainian Constitution of 1710 is the separation of powers and responsibilities, as the document formally divided the government into independent legislative, executive and judicial branches of government – a principle established long before Montesquieu formulated it in the Spirit of the Laws. Legislative power was transferred to the Cossack parliament, called the General Council, which consisted of elected representatives, while executive power remained with the Hetman, but with significant limitations on his powers, which was a unique aspect for those years. Such restrictive measures and dependence on the decisions of the council for the hetman were aimed at preventing autocratic rule and ensuring the rule of law in conditions of a split between the government and the people. The judicial system was also planned to be independent, which eliminated the traditional role of influence of the hetman and senior Cossack leaders as judges and thus guaranteed a fairer trial and conclusions. In addition to the separation of powers and the rule of law over government, the Constitution enshrined various rights and freedoms, for example, it guaranteed citizens the protection of private property and freedom of religion, which played an extremely significant role in Eastern Europe, where there were tensions between Orthodox and Catholics. In addition, it is noteworthy that Orlyk’s text also included accountability and transparency mechanisms: for example, it contained provisions similar to impeachment, allowing the Council to hold the Hetman accountable and even remove him from office for violating the “rights and freedoms” of the people.

Preliminary measures were also introduced to combat the age-old problem of corruption, prohibiting hetmans and colonels from accepting gifts or bribes and demanding that positions be filled through free elections. These progressive elements range from checks and balances to social assistance for soldiers (as provided for in article 8), to religious tolerance in a multi-religious region (Synhaievska, 2024). Such features of the country’s supreme law are far ahead of other European ones, when monarchist regimes dominated the continent, and some still do not have such a developed principle of separation of powers and protection of freedoms (Kopytko & Bashchenko, 2025). Pylyp Orlyk laid the foundations of modern constitutionalism, embodying the ideals of national sovereignty, a system of checks and balances – evidence that the intellectual origins of democracy extended beyond the Cossack possessions of Eastern Europe (Kirichenko and Sokolskaya, 2023). This fact shows that Ukraine and its culture of the early 18th century were part of the vanguard of innovative sociopolitical thought.

Among other things, the constitution of Pylyp Orlyk is of great importance for strengthening Ukrainian statehood and identity formation. Although this document was never fully implemented (given that Orlyk was in exile and Ukraine remained under imperial control), it became a powerful symbol of the Ukrainian people’s desire for statehood, freedom, and cultural development. De facto, this was the first clear plan for the creation of an independent democratic Ukrainian state, which also influenced, to one degree or another, some features of national identity, in particular, love of freedom and disobedience (Strashny, Umland, Lovochkina, Tytarenko, & Naydan, 2024, pp.248-249). Over the following centuries, the Ukrainian intelligentsia and patriots remembered and revered this constitution of 1710 as evidence that Ukraine’s democratic aspirations have deep historical roots, which greatly distinguishes it from, for example, Russia, which has never had democratic positions (Ochoa, 2013). Even in modern Ukraine, the legacy of the Orlyk Constitution is honored – in 2021, on the 30th anniversary of the restoration of Ukraine’s independence, the original Latin manuscript was brought to Ukraine from Sweden for public display, which underlines its role as the cornerstone of Ukraine’s constitutional heritage, thus, Orlyk’s texts have occupied an honorable place in history through the centuries (Mokhonchuk, 2021).

Conclusion

The Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk of 1710 is an exceptionally far-sighted, important and unique document in both Ukrainian and world history, including by proposing a democratic framework for an independent Ukrainian state. Although the Constitution of Orlyk remained only on paper due to the fragmentation of society and the enslavement of Ukraine in the 18th century, through decades and centuries it has become a unifying symbol of national resilience and democracy in Ukraine. Its provisions – from the separation of powers and the rule of law, which limits powers, to the protection of rights and social security – demonstrate an advanced political philosophy, unusually progressive for its era. In fact, based on all the above-mentioned facts, it is fair to assume that the first democratic constitution was proposed by Pylyp Orlyk and is an important milestone on the way to spreading democracy throughout the world.

References

Kopytko, V., & Bashchenko, O. (2025, June 28). Ukraine’s first constitution isn’t even in Ukraine — historian Oleksandr Alfiorov. RBC‑Ukraine. Retrieved July 17, 2025, from https://newsukraine.rbc.ua/interview/ukraine-s-first-constitution-isn-t-even-in-1751102581.html

Mokhonchuk, Y. (2021, June 28). Sweden sends Ukraine copies of Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution on Constitution Day. Kyiv Post. Retrieved from https://www.kyivpost.com/post/7660

Ochoa, Z. K. (2013, December 23). Russia: The democracy that never was. E-International Relations. Retrieved July 17, 2025, from https://www.e-ir.info/2013/12/23/russia-the-democracy-that-never-was/

Pidkupko, T. L. (2023, April 5). Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution — the first Ukrainian constitution. Odesa National Medical University. https://onmedu.edu.ua/konstitucija-pilipa-orlika/

Shevtsova, S. (2021, August 13). Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution: A return after 311 years [Конституція Пилипа Орлика. Повернення через 311 років]. Ukrainian Courier. Retrieved from https://ukurier.gov.ua/uk/articles/konstituciya-pilipa-orlika-povernennya-cherez-311-/

Sokalska, O., & Kyrychenko, V. (2023). “The Treaties and Covenants” of Pylyp Orlyk of 1710: The influence of social and political circumstances on historical discourse. Opera Historica, 24(1), 82–109. Retrieved from https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A5%3A6370309/detailv2?sid=ebsco%3Aplink%3Ascholar&id=ebsco%3Agcd%3A173350787&crl=c&link_origin=scholar.google.com

Strashny, A., Umland, A., Lovochkina, A., Tytarenko, O., & Naydan, M. M. (2024). The Ukrainian Mentality: An Ethno-Psychological, Historical, and Comparative Exploration. ibidem Press. Retrieved from https://emed.library.gov.ua/wp-content/uploads/tainacan-items/50160/149510/The-Ukrainian-Mentality-An-Ethno-Psychological-Historical-and-Comparative-Exploration.pdf

Synhaievska, D. (2024, November 1). From Cossack codes to independence: Tracing Ukraine’s constitutional heritage. UkraineWorld. Retrieved July 17, 2025, from https://ukraineworld.org/en/articles/basics/constitutional-heritage

Subtelny, O. (1990). Pylyp Orlyk in Exile: The Religious Dimension. Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 14(3/4), 584–592. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41036402

Vasylenko, M. (1958). The Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk. The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the US, 6(4). https://shron1.chtyvo.org.ua/Mykola_Vasylenko/The_Constitution_of_Pylyp_Orlyk_anhl.pdf?

Vovk, O. B. (2010). The Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk: original and its history. Archives of Ukraine, (3–4), 145–166. Retrieved from https://old.archives.gov.ua/Publicat/AU/AU_3_4_2010/14.pdf

Weiss, D. (2023, September–October). Ukraine’s lost capital. Archaeology Magazine. https://archaeology.org/issues/september-october-2023/features/ukraine-baturyn-cossack-capital/

Wilkerson, K. (2023, June 15). The Constitution of Ukraine: Orlyk’s Constitution (1710) – Ahead of Its Time. Sunflower Seeds Ukraine (Blog). Retrieved from sunflowerseedsukraine.orgsunflowerseedsukraine.org