Written by SUSK Canada Summer Job Intern – Daniil Zhelezniak (Saint Mary’s University)

There is a stereotype that Ukraine is an exclusively monoethnic and monoreligious Christian country. However, Ukraine has long been a cultural crossroads, the cradle of religious thought, and home to a rich variety of religions. However, this harmony was won with difficulty and blood over centuries of turbulent history and tragedies on a large scale. This article explores the religious diversity of Ukraine – from ancient pagan traditions to the development of minorities, like Jewish and Islamic communities, the unique cultural mosaic of various peoples of the largest country in Europe, and the trials of religious repression under Soviet rule.

Pagan Roots in the Ukrainian Lands

Pagan customs of pre-Christian times

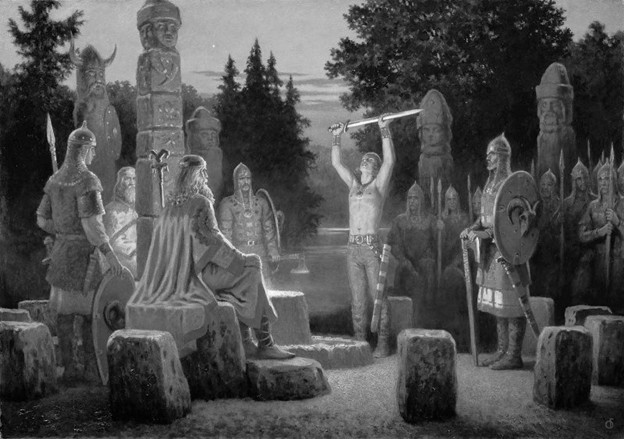

Before the arrival of Christianity, Slavic varieties of paganism dominated the territories of Eastern Europe, including the territories of modern Ukraine. Then the Ancient Slavs worshiped the pantheon of deities associated with the elements and forces of nature and agrarian life. The main and most famous of them was Perun, the god of thunder and war, who was revered as the supreme deity of the early Eastern Slavs (“Perun”, 2023). The importance of Perun is evident in historical chronicles and in the analysis of certain events – for example, in the “Primary Chronicle” it is recorded that as early as 944 A.D., Rus’ princes swore oaths to Perun when concluding treaties with Byzantine (“Ukraine’s Pagan History”, n.d.). Other gods were also worshipped, such as Dazhbog (the god of the sun) and Veles (associated with cattle and the underworld), as well as many spirits of nature and household, known in folk tradition as berehini (female patron spirits) and evil spirits or demons (Uzelac, 2023). Pagan rituals have been preserved for centuries and applied in various areas of life, including agriculture, leaving an indelible mark on modern Ukrainian culture. Even after the official adoption of Christianity, ordinary people continued to secretly worship pagan deities and nature spirits, even mixing them with Christian traditions and values. Even many funeral customs reflected these traditional beliefs – for example, it was customary to bury people with their belongings and hold a common holiday a year after death, which in fact has its roots in the pre-Christian tradition. To this day, elements of ancient Slavic paganism have been preserved in Ukrainian folklore and festive events, so the well-known midsummer festival of Ivan Kupala, which pays special attention to rituals related to water, fire and vegetation, is one of the most striking examples of an already Christian holiday (the Nativity of John the Baptist), enriched with pre-Christian customs.

In fact, when Prince Volodymyr the Great ordered the Christianization of Kyiv in 988, people reportedly wept when the idol of Perun was torn down and thrown into the Dnipro River. It is a clear illustration of how important it was and how deeply rooted the old religion was. Nowadays, there is even a slight revival of the Slavic Rodnovir movements, and in the late 1990s a neo-Pagan society called the Rune of Perun was established in Donetsk, reflecting a resurgence of interest in pre-Christian spirituality in independent Ukraine. In addition, in different regions of Ukraine, you can find the legacy of those eras, like Bogit and Babina Valley in the Ternopil Oblast, Kamyanaya grave and Khortytsya Island in the Zaporizhia or Mavryn Maidan in the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast.

The Christianization of Kyivan Rus

The Baptism of Rus’

The baptism of Rus in 988 was a turning point that determined the further development of the Ukrainian religion, people, and even the geopolitical balance of power for centuries to come. Prince Volodymyr the Great of Kyivan Rus adopted Eastern Christianity from the Byzantine Empire, the superpower of that era, and declared it the new state religion, abolishing official pagan worship services (Dzhulai, 2024). This transformation actually equalized Kyivan Rus with Byzantium (the Eastern Orthodox Church), but before the baptism, there were even ideas about Catholicization and Islamization of these lands, depending on the trade and economic potential as well (“988 Vladimir Adopts Christianity”, n.d.). In addition, it is essential to note that the Christianization of Ukraine was not an immediate process, but rather a gradual one, and it took centuries for Christianity to spread to all Ukrainian lands (Dzhulai, 2024). Also, in the first centuries of our era, early Christian activity was observed on the Crimean peninsula, which was then located outside Kyivan Rus: the ancient city of Chersonesos (in Crimea) sheltered Christian exiles and by the fourth century even had a bishop, which indicates the historical importance of the region (Klenina, 2016). In fact, there are rumors that Volodymyr himself was baptized in Chersonesos before bringing the new faith to Kyiv (Windhausen, 2016). The adoption of Byzantine Christianity also meant that the Kyivan Church came under the religious jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople (Kovalenko, 2025). For centuries, the Metropolitan of Kyiv was appointed by Constantinople, and rituals and church art in Ukraine corresponded to the traditions of Eastern Orthodoxy (the Byzantine Rite). Kyivan Rus, which converted to Christianity from the East, remained Orthodox and joined the sphere of influence of Constantinople. However, over time, the western regions of Ukraine also felt the pull of Catholic Europe. Since the 14th century, most of western Ukraine (Galicia, Volhynia, etc.) has been under the rule of Catholic powers, primarily as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) (Hajda, Yerofeyev, Makuch, Zasenko, Kryzhanivsky, Stebelsky, 2025). Over time, a unique religious mix developed in Western Ukraine, such as the Union of Brest in 1596, which is studied in detail in Ukrainian schools, according to which a significant part of the Ukrainian Orthodox clergy entered into communion with the Pope, while maintaining Eastern liturgical practices (Sysyn, n.d.). Thus, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, important for the Western regions of the country, was created, which recognized the authority of the Pope, but retained the Byzantine rite and the Church Slavonic language. Thus, by the beginning of modern times, Ukraine was home to many Christian traditions: the majority were Eastern Orthodox, a significant presence of Greek Catholics in the west, small groups of Roman Catholics (especially Poles and Hungarians in cities), and at a certain point, various Protestant minorities began to gain importance (Dickinson, 2020). Each tradition often corresponded to different ethnic communities on Ukrainian lands – for example, Orthodox Christians to ethnic Ukrainians, Russians, Belarusians, Greeks, Bulgarians, Romanians, Moldovans, Gagauz, Georgians, etc; Greek Catholics to Ukrainians in Galicia; Roman Catholics to Poles and Slovaks, and later Protestants to Hungarians, Germans, or other settlers.

The church is located in the region of compact residence of Bulgarians in the Odesa region

Former St. Nicholas Church and Trinitarian monastery, Lviv

Roman Catholic Church in Berehove, Zakarpattia, the place of residence of many Hungarians in Ukraine

Judaism in Ukraine: From Early Presence to Hasidic Pilgrimages

The Jewish presence on Ukrainian lands dates back many centuries and has had a profound impact on the cultural landscape of the country. In fact, Judaism was on the territory of present-day Ukraine even before Christianity, as in ancient times there were Jewish communities of refugees from the Middle East in the Greek colonies on the Black Sea coast and in Crimea (Dzhulai, 2024). Archaeological finds in ancient Crimean cities (for example, the synagogue in Panticapaeum, modern Kerch) indicate that the Jewish community operated there at least until the early Byzantine era (Schuster, 2024). Another notable chapter is the Khazar Khaganate during the early Middle Ages. The Khazars were a Turkic people who controlled a vast territory of southeastern Ukraine in the 8th-10th centuries and are unique in that the Khazar elite converted to Judaism in the 9th century (Miller, n.d.). This unusual state adoption of Judaism left a legacy: after the fall of the Khazars, the Jewish descendants, lived in Kyiv and other cities, which indicates a constant Jewish presence even before the emergence of Kyivan Rus (Kubijovyč & Markus, 1988). Jewish life flourished in later centuries, especially during the relatively tolerant rule of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (XVI-XVIII centuries). In many cities of Right-bank Ukraine and Galicia, a significant Jewish population, most often of the Ashkenazi origin, was engaged in trade, crafts, and estate management (Teter, 2021). However, Jews also suffered significantly during periods of conflict between Cossacks and Poles (Mikaberidze, 2013, pp.100-101).

At the same time, Hasidism, a mystical Jewish revivalist movement, was born on Ukrainian soil. In the mid-1700s, Yisrael ben Eliezer (Baal Shem Tov) from Podilia Region founded the Hasidic approach, and one of the main Hasidic traditions is even named after the Ukrainian city of Bratslav (Breslov), where they originated (Marchenko, 2023). To this day, Ukraine remains a vital center of Hasidic pilgrimage, primarily Medzhybizh in the Khmelnytskyi Oblast, the burial place of the Baal Shem Tov, the cradle of Hasidism, and especially Uman, Cherkasy Oblast, where the grave of Rabbi Nachman, the founder of Breslov Hasidism, is located (Berz & Morantz, 2024). Every year during Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year), tens of thousands of Hasidic Jews from all over the world come to Uman to pray at Rabbi Nachman’s grave, a tradition that turns the small town into a vibrant international pilgrimage destination, even during wartime (Palikot, 2022).

Hasidic pilgrims in Uman on Rosh Hashanah

By the 19th century, the territory of present-day Ukraine (then divided between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires) was home to the largest Jewish settlements in the world, so in many cities of Ukraine, Jews even made up the majority (Veidlinger, 2012). Cities like Kyiv, Zhytomyr, Chernihiv, Vinnytsia, Poltava, Cherkasy, Lviv, Uzhhorod, Kharkiv, and Odessa have become thriving centers of Jewish commerce, culture, and thought. The cosmopolitan and multicultural port city of Odessa had a significant Ashkenazi Jewish population (37% of the population) and contributed to the development of humor, literature and commerce (Rosenberg, 2022). Dnipro (Dnipropetrovsk), another major city, was also home to a significant Jewish community and has recently become known for the Menorah Center, which opened in 2012 as the world’s largest Jewish community center and museum complex of the Holocaust (Runyan, 2012). The opening of the Menorah Center in independent Ukraine symbolizes the rebirth of Jewish life and memory decades after the horrors of the Russian Empire discrimination, Soviet repression, and the Holocaust. Under Russian rule, the majority of Ukrainian Jews were subjected to pressure and lived in the “Pale of Settlement”, the only region where the Russian Empire allowed Jews to live permanently (Shayevich, 2023). During the Holocaust, Nazi occupiers and local collaborators killed about 1.5 million Jews in Ukraine, mass shootings in places like Babyn Yar in Kyiv have destroyed entire communities (Popowycz, 2022). The subsequent Soviet regime, with its state-imposed atheism and anti-Semitic restrictions, further suppressed Jewish religious practice – many synagogues that survived the war were closed, and open worship was discouraged (Salomoni, 2010). As a result, by the time Ukraine gained independence in 1991, its Jewish community was only a fraction of its pre-war size. However, after independence, there was a notable Jewish revival in the country, and today Ukraine is home to one of the largest Jewish communities in Europe, estimated at hundreds of thousands of people (Boyd, 2022). Jewish schools, the restoration of synagogues, cultural festivals, and charitable organizations are now open all over Ukraine. Moreover, many artists and politicians are Jews, even the president of the country, Volodymyr Zelensky, is an Ashkenazi Jew, which demonstrates the tolerance of the society of democratic Ukraine, and it helps to strengthen relations with the State of Israel (Beckerman, 2022).

The Jewish Menorah Center in Dnipro, the biggest Jewish community center in the world

Islam and the Crimean Tatars

The third Abrahamic religion, Islam, also has a deep history in Ukraine, especially in the southern regions and Crimea. The advent of Islam was accompanied by a series of invasions and settlements that took place over the millennia. At first, there were minor occurrences – for example, during the Khazar Khaganate, although the ruling class of the Khazars converted to Judaism, there were Muslims because of contacts with neighboring Islamic states of those years. However, Islam really established itself in the 13th century, when the Golden Horde (the western Mongol Empire) conquered most of the region (Favereau, 2021). During the Mongol-Tatar rule, the first mosques appeared on Ukrainian soil, and active ties were established between the region and the wider Muslim world. After the collapse of the Golden Horde in the 15th century, the Crimean Khanate emerged as a Turkic state under the protection of the Ottoman Empire, which was inhabited by Sunni Muslims and has become the main bearers of Islam in Ukraine to this day (Hryshko, 2023). For centuries, the Crimean Khanate controlled Crimea and the surrounding steppe lands of the Tavriya region, in addition to the Ottoman occupation of the Black Sea region, Islam was firmly rooted there. By the beginning of modern times, dozens of mosques, madrasahs (Islamic schools), and Islamic courts were operating throughout the Crimean Peninsula and the Tavriya steppe. The influence of Islam in Ukraine waned in the 18th and 19th centuries as the Russian Empire expanded southward (Bebler, 2015). The annexation of Crimea by Russia in 1783 led to a mass exodus of Muslims, many Crimean Tatars fled or were deported to Ottoman lands during the 1800s, which drastically reduced the Muslim population (Kulinich, 2025). And even now, there is a large community of Crimean Tatars in modern Turkey, including quite influential ones who provide assistance to their people abroad (Aydin, 2002). In regions such as Budjak (Bessarabia), entire communities of nomadic Nogai Tatars were expelled after Russia established control in 1812, resettling in Turkey or the Caucasus (Dyck, Staples & Epp, 2015). Nevertheless, the majority of the Crimean Tatar population remained in Crimea, under Russian rule, faced pressure to assimilate or migrate. Unfortunately, the 20th century brought even more severe repression, as during Stalin’s rule, the Crimean Tatar language was banned from public life, hundreds of mosques were closed or destroyed (Green, 2022). Then, in 1944 the mass deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar people from their homeland to Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan began. In Central Asia, almost half of the Crimean Tatars died of starvation, oppression, or disease (Richardson, 2024). This act of genocide decimated Crimea’s indigenous Muslim community for decades; the surviving Tatars were only allowed to return in the late 1980s.

Palace of the Crimean Khan near Bakhchysarai. Carlo Bossoli, 1857

In independent Ukraine, Islam is undergoing a gradual revival, with restored mosques and new Islamic centers serving communities both in Crimea and in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odessa, and other regions. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, many Crimean Tatars fled to mainland Ukraine and abroad, where they joined existing Muslim communities (Muratova, 2024). It is estimated that before the full-scale war, about 1 million Muslims lived in the territories of Ukraine – Crimean Tatars, Volga Tatars, Azerbaijanis, Chechens, Afghans, Arabs, and Turks (Trach, 2016).

Arab Cultural Center, mosque in Odesa

Religion Under the Soviet Regime

As it was already mentioned in the SUSK’s article on life in the USSR, in Ukraine, which had a rich religious life before the advent of communism (Orthodox Christians, Greek Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Protestants, etc.), during the Soviet period, there were very repressive restrictions on religious freedom. Even after Stalin’s era, open worship became possible only with strict regulation and the introduction of the aforementioned system of informers, and many religious communities were driven underground and often branded as sects. Despite the course of de-Stalinization in the 1960s, a particularly aggressive anti-religious campaign was conducted under Nikita Khrushchev from 1959 to 1964, during which the Soviet government closed thousands of religious buildings (Van den Bercken, 1988, pp. 114-115). Monasteries were closed, seminaries were reduced, and many clergymen were forced to leave the clergy. Of the 1,500 mosques operating in the USSR in 1959, only about 400 remained by the mid-1960s (Khrushchev closed about 1,100 of them). Also, sad things happened to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC), which is very important for western Ukraine: in 1946 it was completely banned by Stalin, and its clergy were imprisoned (Diuk, 2016). Thus, in Lviv, Ternopil, and Ivano-Frankivsk oblasts throughout the Soviet era, Greek Catholic worship existed only in secret, underground, until legalization in 1989, which, undoubtedly, can be considered as a suppression of the Ukrainian identity. Moreover, young people were not encouraged to attend church – parents were afraid that their children would face discrimination at school or at work if it became known that they were religious. There have been cases where simply attending church could undermine career prospects, especially for party members or those in positions of responsibility. The regime promoted “scientific atheism” – ubiquitous lectures and the media ridiculed religious “superstitions” (Froese, 2004, pp.40-45). It was also difficult to own religious literature (Bibles, Korans, Torahs, etc.), since there were few religious publications, and the import of such texts was illegal. It was only by the 1970s that a kind of balance and limited truce was established – the state allowed a small number of churches to function, but under its control. The USSR prided itself on having “freedom of conscience” in its constitution, but in practice that freedom was only for those whose conscience aligned with Marxist–Leninist atheism.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I would like to note that the religious diversity of Ukraine is the result of a long and complex history that goes back to ancient times. The country was the birthplace of ancient pagan traditions, a thousand-year-old Orthodoxy , the emergence of Ukrainian Catholic and Protestant communities, one of the richest Jewish legacies in the world, and a Muslim culture in Crimea. This tapestry suffered from foreign domination and was seriously torn apart by the atheistic Soviet regime, but it survived, despite the consequences visible to this day. For the Ukrainian population and other friends of Ukraine, this diverse heritage is a source of pride, illustrating the enduring spirit of tolerance and the deep roots of freedom that continue to nourish Ukrainian society and which, among other things, is enshrined in the secular, democratic constitution.

REFERENCES

988 Vladimir Adopts Christianity. (n.d.). Christian History Institute. Retrieved from https://christianhistoryinstitute.org/magazine/article/vladimir-adopts-christianity

Aydin, F.T. (2002, January 8). Crimean Turk-Tatars [1]: Crimean Tatar Diaspora Nationalism in Turkey. International Committee for Crimea. Retrieved from https://www.iccrimea.org/scholarly/aydin.html

Bebler, A. (2015, June 28). The Russian-Ukrainian conflict over Crimea. IFIMES. Retrieved from https://www.ifimes.org/en/researches/the-russian-ukrainian-conflict-over-crimea/3829

Beckerman, G. (2022, February 27). How Zelensky Gave the World a Jewish Hero. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2022/02/zelensky-ukraine-president-jewish-hero/622945/

Berz, K.L. & Morantz, A. (2024, March 28). Journey Beyond Tradition. Azrieli Foundation. Retrieved from https://azrielifoundation.org/aperio-magazine/journey-beyond-tradition/

Boyd, J. (2022, March 10). The number of Jews living in Ukraine is much lower than estimated, and will only decline from here. Institute for Jewish Policy Research. Retrieved from https://www.jpr.org.uk/

Dickinson, P. (2020, February 13). Nation-building Ukraine marks a year of Orthodox independence. Atlantic Council. Retrieved from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/nation-building-ukraine-marks-a-year-of-orthodox-independence/

Diuk, N.M. (2016, March 8). The Church That Stalin Couldn’t Kill: Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church Thrives Seventy Years after Forced Reunification. Atlantic Council.

Retrieved from

https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/the-church-that-stalin-couldn-t-kill-ukrainian-greek-catholic-church-thrives-seventy-years-after-forced-reunification/

Dzhulai, L. (2024, July 31). Ukraine’s Religious Diversity: Then and Now. Ukraine World. Retrieved from https://ukraineworld.org/en/articles/basics/ukraines-rel-diversity#:~:text=One%20of%20the%20most%20important,which%20was%20brought%20from%20Constantinople

Dyck, H., Staples, J., & Epp, I. (2015). I. The Nogai Tatars in Russia. Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe: Letters and Papers of Johann Cornies. University of Toronto Press. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442622371-021

Favereau, M. (2021, June 11). How the (Much Maligned) Mongol Horde Helped Create Russian Civilization. Quillette. Retrieved from https://quillette.com/2021/06/11/how-the-much-maligned-mongol-horde-helped-create-russian-civilization/

Froese, P. (2004). Forced secularization in Soviet Russia: Why an atheistic monopoly failed. Journal for the scientific study of religion, 43(1), 35-50. Retrieved from https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/74490014/document-libre.pdf?

Green, M.A. (2022, September 13). Crimean Tatars and Russification. Wilson Center. Retrieved from https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/crimean-tatars-and-russification

Hajda, L.A., Yerofeyev, I.A., Makuch, A., Zasenko, O.E., Kryzhanivsky, S.A., Stebelsky, I. (2025, August 13). Ukraine. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Ukraine\

Hryshko, A. (2023, August 10). Crimea Unravelled: a Deep Dive Into the History, Russian Occupation, and Ukraine. Ukraine World. Retrieved from https://ukraineworld.org/en/articles/infowatch/crimea

Klenina, E. (2016). THE EARLY-CHRISTIAN CHURCHES ARCHITECTURE OF CHERSONESOS IN TAURICA. In: Acta XVI Congressvs Internationalis Archaeologiae Christianae. Pars II. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/31062474/THE_EARLY_CHRISTIAN_CHURCHES_ARCHITECTURE_OF_CHERSONESOS_IN_TAURICA_In_Acta_XVI_Congressvs_Internationalis_Archaeologiae_Christianae_Pars_II_2016_Pp_2255_2280_ISBN_978_88_85911_65_1

Kovalenko, I. (2025, July 29). Kyiv Built Cathedrals when Moscow Was Still a Forest – Eastern Slavic Christianity, Explained. Ukraine World. Retrieved from https://ukraineworld.org/en/articles/analysis/kyiv-built-cathedrals-when-moscow-was-still-forest#:~:text=Christianity%20arrived%20in%20the%20territory,cultural%20development%20in%20the%20region.

Kubijovyč, V., & Markus, V. (1988). Jews. Encyclopedia of Ukraine (Vol. 2). Retrieved from https://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CJ%5CE%5CJews.htm

Kulinich, M. (2025, March 27). Genocide of the Crimean Tatars: an ongoing crime. Ukraїner. Retrieved from https://www.ukrainer.net/en/genocide-of-the-crimean-tatars/

Marchenko, A. (2023, December 7). Return and Redemption. Copernico. Retrieved from https://www.copernico.eu/en/articles/return-and-redemption-hasidic-pilgrimages-contemporary-poland-and-ukraine

Mikaberidze, A. (2013). Atrocities, massacres, and war crimes: An encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/5547491

Miller, Y.A. (n.d.). Ukraine and the Jews. Aish. Retrieved from https://aish.com/ukraine-and-the-jews-12-facts/

Muratova, E. (2024, March 18). The Lives and Hopes of Crimean Tatars after the 2014 Annexation. Centre for East European and International Studies. Retrieved from https://www.zois-berlin.de/en/publications/zois-spotlight/the-lives-and-hopes-of-crimean-tatars-after-the-2014-annexation

Palikot, A. (2022, September 27). For Hasidic Jews, A Pilgrimage To Wartime Ukraine. Radio Liberty. Retrieved from https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-war-hasidic-jews-uman-pilgrimage-russia/32054731.html

Perun. (2023, October 22). Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Perun

Ph.: Feschenko, A. (2023, September 13). Скільки хасидів уже прибуло в Умань, попри заклики відмовитися від паломництва [How many Hasidim have already arrived in Uman despite calls to cancel the pilgrimage]. Glavcom. Retrieved from https://glavcom.ua/country/incidents/skilki-khasidiv-uzhe-pribulo-v-uman-popri-zakliki-vidmovitisja-vid-palomnitstva-956160.html

Ph.: Inclusive Travels in Ukraine. (n.d.). Костел Воздвиження Святого Хреста, Берегове [Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, Berehove]. Travels in Ukraine. Retrieved from https://travels.in.ua/uk-UA/object/458/kostel-vozdvyzhennya-svyatoho-khresta

Ph.: Khvist, V. (2018, July 27). The Baptism of Rus’ and the development of historical thought in the Old Rus’ era [Ukraine title: Хрещення Русі та розвиток історичної думки в Давньоруську добу; National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine. Retrieved from https://nubip.edu.ua/node/49236

Ph.: Malenkov, R. (n.d.). Kyrnychky. Fontay Fey [Kyrnychky: The Fountain of Fairies]. Ukraina Incognita. Retrieved from https://ukrainaincognita.com/mista/kyrnychky-fontay-fey

Ph.: President took part in the ceremony of lighting Hanukkah candles. (2023, December 7). President of Ukraine. Retrieved from https://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/glava-derzhavi-vzyav-uchast-u-ceremoniyi-zapalennya-hanukaln-87565

Ph.: Yakubovych, M. (2023, June 8). Earth and faith: What is the specificity of Crimean Tatar Islam? Ukrainian Week. Retrieved from https://tyzhden.ua/zemlia-ta-vira-u-chomu-poliahaie-spetsyfika-krymskotatarskoho-islamu/

Ph.: Aрабський культурний центр – мечеть, яка збирає мусульман та усіх, хто цікавиться ісламською культурою [Arab Cultural Center – a mosque that gathers Muslims and all those interested in Islamic culture]. (n.d.). А Sovinyon. Retrieved from https://www.sovinyon.net/info/arabskij-kulturnyj-centr

Ph.: Екскурсія до культурно-ділового центру “Менора” [Excursion to the Cultural and Business Center “Menorah”]. (n.d.). Visit Dnipro. Retrieved from https://visitdnipro.com/ekskursii-po-dnepru/ekskursiia-do-kulturno-dilovoho-tsentru-menora/

Ph.: “Омофор твій нам оборона”: 6 грудня — день святого Миколая [“Your Omophor is our protection”: St. Nicholas Day on December 6]. (2023, December 5). Dukhоvna Velych Lʹvova. Retrieved from https://velychlviv.com/omofor-tvij-nam-oborona-6-grudnya-den-svyatogo-mykolaya/

Ph.: Язичництво – що це таке і хто такі язичники простими словами [What is paganism and who are pagans, in simple terms]. (n.d.). Termin.in.ua. Retrieved from https://termin.in.ua/yazychnytstvo/

Popowycz, J. (2022, January 24). The “Holocaust by Bullets” in Ukraine. The National WW2 Museum New Orleans. Retrieved from https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/ukraine-holocaust

Richardson, J. (2024, May 17). Time to recognise the Crimean Tatar genocide. The Lowy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/time-recognise-crimean-tatar-genocide

Rosenberg, Y. (2022, March 10). Echoes From Odessa, the Onetime Jewish Metropolis Now Menaced by Putin. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/newsletters/archive/2022/03/odessa-jews-ukraine-putin-invasion-tchernowitz/676809/

Runyan, T. (2012, October 17). World’s Largest Jewish Center Opens in Dnepropetrovsk. Chabad. Retrieved from https://www.chabad.org/news/article_cdo/aid/1991671/jewish/Largest-Jewish-Center-Opens.htm

Salomoni, A. (2010, April 1). State-Sponsored Anti-Semitism in Postwar USSR. CDEC. Retrieved from https://www.quest-cdecjournal.it/state-sponsored-anti-semitism-in-postwar-ussr-studies-and-research-perspectives/

Schuster, R. (2024, November 27). Excavations of Early Synagogue by Black Sea Find Jewish Neighborhood. Haaretz. Retrieved from https://www.haaretz.com/archaeology/2024-11-27/ty-article-magazine/excavations-of-early-synagogue-by-black-sea-find-whole-jewish-neighborhood/00000193-68d0-dd83-afdf-fff229ce0000

Shayevich, B. (2023, September 6). A New World. The Nation. Retrieved from https://www.thenation.com/article/world/soviet-jews-pale-settlement/

Sysyn, F.E. (n.d.). Union of Brest (1596). Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved from: https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/union-brest-1596

Teter, M. (2021, December 8). ‘Jews in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: An Embedded Diaspora’, in Hasia R. Diner (ed.). Oxford Academic. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190240943.013.27

Trach, N. (2016, February 11). Ukrainian Muslims root for Ukraine. The Kyiv Post. Retrieved from https://www.kyivpost.com/post/8964

Ukraine’s Pagan History. (n.d.). Ukraine.com. Retrieved from https://www.ukraine.com/blog/ukraines-pagan-history/#:~:text=Perun%2C%20the%20god%20of%20thunder%2C,replaced%20Perun%20with%20Saint%20Elijah

Uzelac, V. (2023, May 15). Slavic Paganism: Mythology, Gods, Creatures & Monsters. CultureFrontier.

Van den Bercken, W. (1988, December 31). Ideology and Atheism in the Soviet Union. De Gruyter. Retrieved from

https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110857375/html

Veidlinger, J. (2012, July 3). Jewish Public Culture in Late Imperial Russia. CDEC. Retrieved from https://www.quest-cdecjournal.it/jewish-public-culture-in-late-imperial-russia/

Windhausen, J. (2022). Baptism of Vladimir I. EBSCO. Retrieved from https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/baptism-vladimir-i#:~:text=The%20Baptism%20of%20Vladimir%20I,blend%20of%20existing%20pagan%20traditions.