Written by SUSK Canada Summer Job Intern – Daniil Zhelezniak (Saint Mary’s University)

Introduction

One of the most prominent, important, and well-known national minorities in Ukraine is the Crimean Tatars. This indigenous Turkic people of Crimea and the Black Sea region, whose identity and history are closely intertwined with the history of Ukraine’s own struggle and resilience, thereby adding diversity and richness to the country’s overall culture. Over the centuries, they have endured conquests, exile, and repression, including the annexation of their homeland by the Russian Empire, genocide during the Soviet era, and the modern suppression of identity and the Russian occupation of Crimea. This article provides an institutional explainer and chronology of the Crimean Tatar history, self-government, and their crucial role in Ukraine after 1991, especially after 2014, and highlights why their recognition and protection of interests are important.

”Homeland or death, we are at homeland”. Crimea.

Origins and Early History of the Crimean Tatars

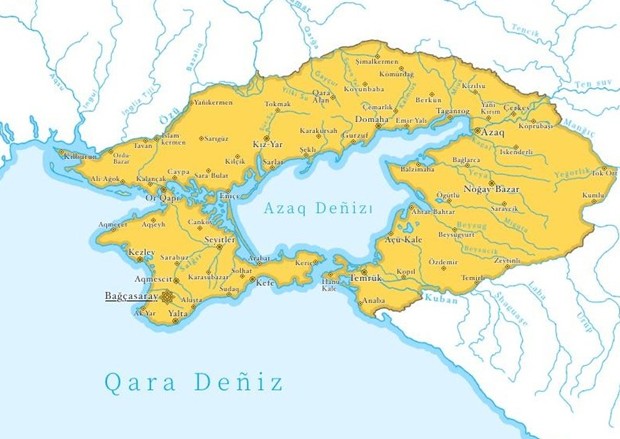

The Crimean Tatars trace their history back to the 13th-century Turkic Golden Horde and are indigenous to the Crimean Peninsula and the surrounding Black Sea steppes (also known as the Tavria region) (“The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica”, 2025). Tatars, like many other Turkic peoples, originally spread from Central Asia, migrated, and eventually settled in the Black Sea region (Baigasin, 2024). By that time, a regional identity had been shaped over the centuries by Greeks, Armenians, Goths, Huns, Alans, Khazars, as well as Scythians, Cimmerians, and Taurians who had lived in antiquity (Zinedine, 2020). In 1441, the Crimean Khanate was founded, a Muslim state centered in Bakhchysarai, a city in the south of the peninsula, which flourished for more than three centuries (Gubernskyi, 2016). By the way, the word Bakhchysarai itself, like the word Crimea, is of Tatar origin; Bağçasaray means “palace-garden,” and Qırım (Crimea) means protection or defense, which actually reflects the history of the region (Allworth, 1998, pp.5-7). The Khanate, often allied with the fraternal Ottoman Empire, exercised significant control over Crimea and parts of modern southern Ukraine. By the 18th century, Crimean Tatars still made up the vast majority of the Crimean population – about 95% in the 1770s (Lapatina, 2023). Along with them, the peninsula was also home to smaller ethno-religious groups such as the Karaites (a Turkic-speaking community professing Judaism) and the Krymchaks (another Jewish group), who contributed to its diverse cultural and religious landscape (Kascian, 2018).

Map of the Crimean Khaganate in the Crimean Tatar language

This rule of the Khanate ended with the arrival of the Russian Empire and the annexation of Crimea by Catherine the Great in 1783, after which Russian rule launched a campaign to destroy the presence of Crimean Tatar identity and culture (Gutterman, 2025). In the context of the numerous wars with the Turkic Ottoman Empire, Catherine II forced the mass expulsion of the Crimean Tatars, actively resettling Russian nobles there, and even renamed cities and villages (Kezlev became Yevpatoria, Aqyar – Sevastopol, Aqmescit became Simferopol) to create a new historical narrative (Kulinich, 2025). In just ten years after the annexation, almost half of the population – about 330,000 Crimean Tatars – were sent into exile to the Ottoman Empire, where their community developed further (Lapatina, 2023). After the Crimean War (1853-1856), which ended in victory for the Turks and their allies, new waves of emigration followed. By the end of the 19th century, the number of Crimean Tatars had decreased to about a quarter of the inhabitants of Crimea, and the diaspora in Turkey had become their largest community abroad. In modern Turkey, at least a million people are of Crimean Tatar origin, and according to other studies, the number could be as high as 5 million, which is almost 20 times the population of the Crimean Peninsula itself (Jankowski, 2000). As a result of the Crimean War, although Russia lost parts of Bessarabia, it retained Crimea, where it began to increase pressure on local Islamic communities. This imperial legacy of oppression set the foundation for more calamity in the 20th century.

Palace of the Crimean Khan near Bakhchysarai. Carlo Bossoli, 1857

Soviet Era: Autonomy and the Deportation

After the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the de facto collapse of the empire, the Crimean Tatars briefly proclaimed the independent Crimean People’s Republic, the first Islamic democratic state, seeking self-determination against the backdrop of general chaos and the growth of national movements (Starodubtsev, 2023). This experiment was thwarted during the subsequent Russian Civil War, and in 1921, the Soviets formed the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, recognizing the Crimean Tatars as a titular indigenous nation (Williams, 2015, pp. 57-88). In the early stages of Soviet politics, special attention was paid to class differences rather than ethnic ones, but Stalin’s rule reversed these gains. The 1930s brought not only industrial development to Crimea, but also brutal collectivization and purges that led to the deaths of tens of thousands of Crimean Tatars. Then came the most traumatic, cruel, and unfair incident in the history of the Crimean Tatar people: the famous mass deportation of 1944.

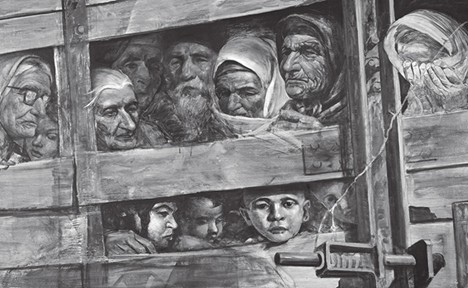

During World War II, in May 1944, after the liberation of the peninsula from German troops, on the instructions of Joseph Stalin, the entire Crimean Tatar population was forcibly expelled from their homeland in a matter of days (Aurélie, 2008). The Soviet authorities falsely accused the Crimean Tatars of collaborating with the Nazis en masse, using this as a pretext for what is now being actively recognized as an act of genocide. The deportees, including many women and children, were sent to remote parts of the USSR, mainly in Central Asia (Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan), where the Crimean Tatars endured terrible hardships. It is estimated that between one-fifth and almost half of them died of starvation, disease, and exhaustion during transportation or during the first years of their stay in deportation (Kulinich, 2025). It was particularly unfair that while the Crimean Tatar soldiers of the Soviet Army fought valiantly against Nazi Germany, their families were sent to “special settlements” surrounded by barbed wire.

Crimean Tatars in Central Asia on cotton harvesting

After the deportation (which was called “Sürgünlik” in Crimean Tatar), the Soviet authorities erased the remaining traces of the Crimean Tatar heritage in Crimea. The Crimean ASSR was abolished; its status was lowered to that of a province, and the Kremlin repopulated Crimea with immigrants from other republics of the USSR (Synhaievska, 2025). Hundreds of Tatar mosques, cemeteries, and cultural monuments were destroyed, and propaganda demonized the Crimean Tatars as “traitors”, “Nazi collaborators” to justify their extermination. For decades, Crimean Tatars were not allowed to return home, making them one of the few deported peoples in the USSR who were not officially rehabilitated after Stalin’s repressions. Despite these conditions, the Crimean Tatar national movement in exile continued to exist, preserving its identity and tirelessly defending the right to return. Finally, during Mikhail Gorbachev’s liberal reforms in 1989, Moscow recognized that the deportation was a “cruel” act and lifted restrictions, allowing Crimean Tatars to return to Crimea, which had already been part of the Ukrainian SSR for several decades (Lapatina, 2015). To this day, Ukraine (along with countries such as Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Canada) officially recognizes the 1944 mass deportation as an act of violence and genocide (Fratsyvir, 2025).

Return to Crimea and Rebuilding (1989–1991)

The policy of perestroika and glasnost gave a historic turn of fate when the Crimean Tatars began to return to their ancestral homeland, and many heard the truth about the Stalin era. If in 1989 there were only about 38,000 Crimean Tatars living in Crimea, by the beginning of the 21st century their number had increased to about 250,000–300,000 people (“The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica”, 2025). It happened thanks to the mass repatriation from Central Asia, which also experienced turmoil amid the rise of nationalism throughout the Soviet Union. Families sold everything they owned in exile and made long journeys back to Crimea, often finding their old villages razed to the ground and their property occupied by other people. They often had to “huddle” on abandoned land, building new houses from scratch, as local authorities were initially reluctant to allocate land for the Tatars.

The inscription on the poster: “Let violence against any people never be repeated, as it happened to the Crimean Tatars on May 18, 1944”.

1991 was a turning point, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine declared independence, and in Crimea, in those years, the Crimean Tatars convened their historic national assembly (Qurultay) on the Crimean issue for the first time since 1917 (Rayfield, 2014). The Qurultay proclaimed the Crimean Tatars a sovereign people and in 1991 elected a representative governing body, the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, to protect their rights as an ethnic minority of Ukraine. The organization’s first chairman was Mustafa Dzhemilev, a veteran dissident who spent 15 years in Soviet GULAG camps for defending his people’s right to return (Kotsira, 2024). From the very beginning, his mission was to appeal to the Government of Ukraine, the regional authorities of Crimea, and international organizations to restore the status of the Crimean Tatar language.

The Crimean Tatars, however, initially firmly sided with the Ukrainian state, seeing it as their best guarantor of security after returning to the rather pro-Russian Crimea. This unification laid the foundation for creating a unique bond: the Crimean Tatars linked their future with an independent Ukraine, while Ukraine recognizes the Crimean Tatars as an integral part of its national identity.

By the end of the 1990s, the Crimean Tatars had also gained representation at the national level. Dzhemilev and another leader of the Mejlis, Refat Chubarov, joined the Ukrainian parliament in 1998, defending the Crimean Tatars (Chervonenko, 2016). In addition, Dzhemilev himself, who is now over 80, still remains a member of parliament. Nevertheless, the progress of unity has been gradual – for example, it was only in 2010 that the Government of Ukraine began allocating regular funding to the needs of the Crimean Tatar community, and it was only in 2014 that their representative bodies received official recognition (Humber, 2019, pp.3-4). Nevertheless, the post-1991 era allowed Crimean Tatars to finally rebuild their lives in Crimea: to revive their language and schools, open mosques, and reassert their identity after decades of absence.

Crimean Tatar Leader Mustafa Dzhemilev and President of the Republic of Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

Mejlis and Crimean Tatar Self-Governance Explained

The Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People is the central institution of self-government of the Crimean Tatar people, which performs the functions of an executive body between sessions of the Qurultay, a national congress of 250-350 elected delegates (Coalson, 2014). The Qurultay acts as the parliament that determines strategy, while the 33-member Mejlis manages day-to-day affairs, including education, culture, land rights, and political representation. The leadership belongs to the chairman of the Mejlis, Mustafa Dzhemilev (1991-2013), and since 2013 to Refat Chubarov, who became an international exponent of the aspirations of the Crimean Tatar people.

Unfortunately, for decades, the Mejlis operated without an official legal status, but it was de facto recognized by Kyiv as legitimate in March 2014, after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, approving the Crimean Tatars as an indigenous people and providing advisory functions to the leaders of the Mejlis (Babin, Grinenko, & Prykhodko, 2019). This recognition contradicts Russia’s position: in 2016, the occupation authorities banned the Mejlis as “extremist,” forcing Dzhemilev and Chubarov into exile and jailing MPs such as Akhtem Chiygoz, Ilmi Umerov, and later activist Nariman Dzhelyal (Fishman, 2023).

For the Crimean Tatars, the Mejlis symbolizes both survival and self-determination. In 2017, the International Court of Justice ordered Russia to lift the ban, but Moscow ignored the decision (“Order concerning the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People”, 2017). In 2021, Ukraine increased its support by passing a law that designated the Crimean Tatars as an indigenous people.

“The stronger your repressions, the fiercer our resistance”. Protest in Kyiv under the Russian embassy against the repression of Crimean Tatars, 2014

After 2014: Annexation and Ukraine’s European Future

When Russia illegally annexed Crimea in 2014, it reopened the old wounds of the Crimean Tatars, who had lived freely in their homeland for only 23 years under independent Ukraine. The Mejlis immediately organized resistance: on February 26, 2014, thousands of people rallied in Simferopol in support of Ukraine’s territorial integrity, and leaders of the Crimean Tatar people called for a boycott of the pro-Russian “referendum” (Hembik, 2024). The turnout in the Tatar villages was minimal, which emphasized their rejection of Russian rule. Since then, an estimated 35,000 to 45,000 Crimean Tatars have fled, while most of those who remain are living under repression or quiet dissent (Zhyliaev, 2025). However, they are quietly resisting, preserving the language, teaching history at home, and celebrating days of mourning such as Memorial Day for the Deported and Day of the Crimean Resistance.

On February 26, 2014, a rally of thousands of Crimean Tatars and pro-Ukrainian activists in support of the territorial integrity of Ukraine was held in Simferopol, Crimea

Since the annexation, the Crimean Tatar issue has become central to Ukraine’s diplomatic and moral position against Russian aggression. In 2021, President Volodymyr Zelensky launched the Crimean Platform, a major international initiative jointly led by representatives of the Crimean Tatar people, aimed at drawing the attention of the world community to this topic (Faraponov, 2021). The EU, Western allies, and Turkey supported this, linking the struggle for the rights of the indigenous population of the Crimean Peninsula with the European integration of Ukraine. International recognition and solidarity strengthen the resolve and support the hope of a free return to the homeland under democratic guarantees.

Cultural Contributions to Ukraine and the World

The Crimean Tatars are distinguished by their vibrant cultural heritage, which enriches both Ukraine and the common Turkic culture and has received worldwide recognition. After returning from Stalin’s exile, they became stronger and revived the traditions of folklore, music, cuisine and crafts. Dishes such as chebureks and pilaf (plov), lagman, and samsa, which were also mixed with Uzbek and Kazakh traditions during the deportation, spread far beyond the borders of Crimea (Saliuk, 2024). Another art form is Ornek (ornamental patterning), with intricate ornaments, which was included in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2021 (Chapple, 2021). Ukraine has also supported efforts to save the endangered Crimean Tatar language, with only 60,000 native speakers, through courses, media projects, and a National Commission established in 2023 (Olszański, 2014).

Crimean Tatar food is an integral part of the culture of united Ukraine

Tatars have made a significant contribution to modern Ukrainian culture. Singer Jamala won the Eurovision Song Contest 2016 with the song ”1944″ about deportation, drawing world attention to her story and dispelling myths about Crimea (Armstrong, 2023). Director Nariman Aliyev was recognized for the film “Homeward” (2019), and Akhtem Seitablaev in the film “Kaytarma” (2013) showed the 1944 deportation (Maimur, 2023). These works preserve memory and affirm identity. As one of the commentators noted, “culture for the Crimean Tatars is not just self-identification, but also a struggle for the right to exist”.

In addition to culture, Crimean Tatars contribute to Ukraine’s current struggle. Many young people are volunteering for the army, including the Crimean battalion (Батальйон «Крим»), formed in 2014 (Hunder, 2022). In 2023, Crimean Tatar MP Rustem Umerov was appointed Minister of Defense of Ukraine, reflecting their leadership role (Harding, 2023). President Zelensky has often stressed that protecting the rights of the Crimean Tatar people is key to Ukraine’s European future. Their persistence ensures that Ukraine and its allies will not be able to forget Crimea while maintaining the vision of a free homeland.

President Volodymyr Zelensky and Defense Minister of Crimean Tatar origin – Rustam Umerov

Conclusion

From the steppes of the Crimean Khanate to the meetings of the Ukrainian Parliament in Kyiv and international forums, the Crimean Tatars have gone through an extraordinary history. This journey, marked by their resilience in the fight against oppression, has made them a cornerstone of modern Ukrainian identity and a symbol of defiance against tyranny. Their self-governing bodies, such as the Mejlis, are an example of democratic representation and respect for the rights of indigenous peoples in action, principles that Ukraine defends in its quest for integration with Europe. Culturally, the Crimean Tatars gave Ukraine and the whole world music, art and cuisine, thus enriching the universal diversity. In turn, Ukraine accepted the Crimean Tatars, recognizing them as an indigenous people and partners in building a free future.

Looking ahead, we note that the destinies of the Crimean Tatars and Ukraine are inextricably linked. As long as the Crimean Tatars continue to speak their language, sing their songs and remember their history, they ensure the preservation of the true spirit of Crimea. And as long as Ukraine remains determined to restore the rights of its Tatar sons and daughters, this nation will remain living testimony to the idea that identity can survive even the most difficult times and that justice, albeit belated, will eventually prevail.

REFERENCES

Allworth, E. (1998). The Tatars of Crimea: Return to the homeland: Studies and documents (2nd ed.). Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375120647_Edward_Allworth_THE_TATARS_OF_CRIMEA_RETURN_TO_THE_HOMELAND_1998

Armstrong, K. (2023, November 23). Jamala: Ukrainian Eurovision winner added to Russia’s wanted list. BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-67478220

Aurélie, C. (2008, June 16). Sürgün: The Crimean Tatars’ deportation and exile. SciencesPo. Retrieved from https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/fr/document/suerguen-crimean-tatars-deportation-and-exile.html

Babin, B., Grinenko, O., & Prykhodko, A. (2019). Legal Statute and Perspectives for Indigenous Peoples in Ukraine. IntechOpen. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.85560

Baigasin, B. (2024, September 15). A chronological history of Turkic peoples; from the roots to modern times. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@turkhankz23/a-chronological-history-of-turkic-peoples-from-the-roots-to-modern-times-b435b61a338d

Chapple, A. (2021, December 28). Crimea’s ‘Ornek’ Art Wins UNESCO Listing. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved from https://www.rferl.org/a/ornek-crimea-tradition–unesco-intangible-heritage-ukraine/31629420.html

Chervonenko, V. (2016, May 18). Меджліс: запор, тюрма и эмиграция [Mejlis: ban, prison, and emigration]. BBC News Україна. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/ukrainian/ukraine_in_russian/2016/05/160518_ru_s_mejlis_tatars_history

Coalson, R. (2014, May 5). Explainer: What Is The Crimean Tatar Mejlis?. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved from https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-crimea-tatars-explainer/25373796.html

Faraponov, V. (2021, August 22). Ukraine Opens the Crimean Platform: What To Expect From It. Ukraine World. Retrieved from https://ukraineworld.org/en/articles/opinions/%D1%81rimean-platform

Fishman, D. (2023, March 23). Indigenous people suffer kidnappings, torture, imprisonment due to annexation of Crimea. The Insider. Retrieved from https://theins.ru/en/politics/260302

Fratsyvir, A. (2025, June 20). Dutch parliament recognizes Soviet 1944 deportation of Crimean Tatars as genocide. The Kyiv Independent. Retrieved from https://kyivindependent.com/dutch-parliament-recognizes-1944-deportation-of-crimean-tatars-as-genocide/

Gubernskyi, B. (2016, December 20). Our Bakhchysarai. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty — Krym.Realii. Retrieved from https://ua.krymr.com/a/news/28186192.html

Gutterman, I. (2025, August 19). How Crimea Has Changed Hands Over The Centuries. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved from https://www.rferl.org/a/crimea-ukraine-russia-history/33506266.html

Harding, L. (2023, September 4). Rustem Umerov: who is Ukraine’s next defence minister? The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/sep/04/rustem-umerov-who-is-ukraine-new-next-defence-minister

Hembik, O. (2024, March 18). “Get Out of Here, My Scope Sees Further than Your Camera”, Said the Russian and Stroked His AK Rifle: How Crimea Was Annexed 10 Years Ago. ZABORONA. Retrieved from https://zaborona.com/en/how-crimea-was-annexed-10-years-ago/

Humber, K. (2019). Crimean Tatars and the politics of sovereignty: small state instrumentalization of ethnic minority sovereignty claims in geopolitically disputed territory. Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia. Retrieved from https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0380945

Hunder, M. (2022, June 1). Ukraine’s Muslim Crimea battalion yearns for lost homeland. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukraines-muslim-crimea-battalion-yearns-lost-homeland-2022-06-01/

Jankowski, H. (2000). Crimean Tatars and Noghais in Turkey. International Committee for Crimea. Retrieved from https://www.iccrimea.org/scholarly/jankowski.html

Kascian, K. (2018, November 28). Minority categorization and neglected Judaic diversity: The case of Krymchaks and Karaites. ICELDS. Retrieved from https://www.icelds.org/2018/11/28/minority-categorization-and-neglected-judaic-diversity-the-case-of-krymchaks-and-karaites/

Kotsira, K. (2024, February 18). Long road to Crimea: story of Mustafa Jemilev. Ukrainer. Retrieved from https://www.ukrainer.net/en/long-road-to-crimea-story-of-mustafa-jemilev/

Kulinich, M. (2025, March 27). Genocide of the Crimean Tatars: an ongoing crime. Ukrainer. Retrieved from https://www.ukrainer.net/en/genocide-of-the-crimean-tatars/

Lapatina, A. (2023, October 16). Who are the Crimean Tatars? The Kyiv Independent. Retrieved from https://kyivindependent.com/who-are-the-crimean-tatars/

Maimur, I. (2023, November 8). Top 10 Films about Ukraine. ALLTOPS. Retrieved from https://alltops.com.ua/en/rest-en/top-10-films-about-ukraine/

Order concerning the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People. (2017, April 19). International Court of Justice [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.icj-cij.org/node/202757

Olszański, T. A. (2014). Crimean Tatars after Russia’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula. OSW. Retrieved from https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2014-07-02/crimean-tatars-after-russias-annexation-crimean-peninsula

Ph.: Den’ oportu Krymu rosiys’kiy okupatsiyi: uchasnyky podylylys’ spohadamy [Crimea Resistance Day against the Russian occupation: participants share memories]. (2018, February 26). Hromadske Radio. Retrieved from https://hromadske.radio/news/2018/02/26/den-oporu-krymu-rosiyskiy-okupaciyi-uchasnyky-podilylys-spogadamy

Ph.: Hromenko, S. (2019, May 18). 3 Soviet myths about Crimean Tatars: Deconstruction [Three Soviet myths about Crimean Tatars. Deconstruction]. Istorychna Pravda. Retrieved from https://www.istpravda.com.ua/articles/2019/05/18/155691/

Ph.: Hryhorenko, A. (2018, May 19). On the 74th anniversary of the deportation of Crimean Tatars [До 74-ої річниці депортації кримських татар]. Kyiv Human Rights Protection Group (KhPG). Retrieved from https://khpg.org/1526719894

Ph.: Imbirovska-Syvakivska, L. (2021, August 9). Indigenous peoples of Ukraine: What they love to eat and cook in Crimea – authentic recipes. 24Channel: Smachno (Смачні рецепти). Retrieved from https://smachnonews.24tv.ua/korinni-narodi-ukrayini-etnichni-retsepti-avtentichni-smaki-krimu_n1707738

Ph.: Klymenko, O. (2016, May 18). Повернення кримських татар на Батьківщину. Перші кроки вдома [Return of the Crimean Tatars to the homeland: The first steps at home]. Ukrayinska Pravda. Retrieved from https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2016/05/18/7108898/

Ph.: Roshchyna, E. (2022, March 12). Erdogan met with Dzhemilev. Ukrainska Pravda. Retrieved from https://www.pravda.com.ua/rus/news/2022/03/12/7330732/

Ph.: Yakubovych, M. (2023, June 8). Earth and faith: What is the specificity of Crimean Tatar Islam? Ukrainian Week. Retrieved from https://tyzhden.ua/zemlia-ta-vira-u-chomu-poliahaie-spetsyfika-krymskotatarskoho-islamu/

Ph.: Young Crimean Tatars go missing in annexed Crimea. (2014, October 7). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty – Krym.Realii. Retrieved from https://ua.krymr.com/a/26624198.html

Ph.: Zelensky appoints Umerov as Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council. (n.d.). Suspilne. https://suspilne.media/1069571-zelenskij-priznaciv-umerova-sekretarem-rnbo/

Rayfield, D. (2014, June 21). How the Crimean Tatars have survived. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jun/21/crimean-tatars-struggle-survival

Saliuk, A. (2024, July 6). Crimean Tatar cuisine. Svidomi. Retrieved from https://svidomi.in.ua/en/page/crimean-tatar-cuisine#:~:text=Every%20national%20cuisine%20is%20shaped,deported%2C%20in%20particular%20from%20Uzbekistan.

Starodubtsev, V. (2023, January 6). The People’s Republic of Crimea (1917-1918). Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières. Retrieved from https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article65264

Synhaievska, D. (2025, February 26). How Russia Used Crimea’s Autonomy to Prepare its Annexation. Ukraine World. Retrieved from https://ukraineworld.org/en/articles/opinions/crimea-autonomy-annexation

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (2025, August 19). Crimea. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Crimea

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (2025, July 18). Golden Horde. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Golden-Horde

Williams, B.G. (2015, December). Soviet Homeland: The Nationalization of the Crimean Tatar Identity in the USSR in The Crimean Tatars: From Soviet Genocide to Putin’s Conquest. Oxford Academic. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/book/2312/chapter-abstract/142449049?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Zhyliaev, V. (2025, May 4). Deportation of Crimean Tatars. Creating the illusion of “Russian Crimea”. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@zhyliaevv/deportation-of-crimean-tatars-creating-the-illusion-of-russian-crimea-3f8ee3a818ee

Zinedine, H. (2020, July 7). Ethnogenesis of the Crimean Tatars. Voice Culture. Retrieved from https://culture.voicecrimea.com.ua/en/ethnogenesis-of-the-crimean-tatars/