Written by SUSK Canada Summer Job Intern – Daniil Zhelezniak (Saint Mary’s University)

A fairly well-known story is the placement and suffering of Ukrainians in GULAGs in Siberia and the Far East during the Stalinist terror. However, the little-known but grim fact remains that during World War I, Canada secretly imprisoned thousands of civilians in a network of internment camps across the country. Most of the prisoners were Ukrainians, ordinary immigrants caught in the net of Canada’s military policy against “enemy aliens”. This little-known chapter of Canadian history provides a sobering lesson about how fear, xenophobia, and prejudice can lead to restrictions on civil liberties. This article will examine the history of the internment of Ukrainians in Canada (1914-1920), covering the harsh realities of the camps, ruined lives, and a long road to recognition and reparation.

Historical Context

In August 1914, the First World War began, the British Empire and Canada, as its overseas part, declared war on the German Empire, thereby also ending up at war with its allies like Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. This event caused a great increase in anti-immigrant and even nationalist ideas, so almost immediately suspicion and distrust fell on immigrants from hostile countries living in Canada. Many of these immigrants were Ukrainians from the Austro-Hungarian provinces of Galicia and Bukovyna – technically Austrian citizens, although Ukraine was not an independent country. At that time, almost 170,000 immigrants from Ukraine had already arrived in Canada, having mostly settled in Ontario and the Prairies (Martynowych, 1991, pp.3-4). Just a few weeks after the outbreak of war, the Canadian government issued a proclamation authorizing the arrest and detention of any immigrant from enemy countries if there were “reasonable grounds” to suspect him of disloyalty (Smith, 2013). A week later, Parliament passed a law, War Measures Act, granting the Federal Cabinet expanded powers to restrict civil liberties and detain people without trial during the war (“War Measures Act”, 1914) Under these emergency powers, thousands of civilians in Canada were declared “enemy aliens” (Kordan, 2002, pp. 90-115). Overnight, people who immigrated overseas in search of a better life – Germans, Austrians, Hungarians, and Ukrainians, Czechs, Serbs, Croats, Poles, and others who were not directly involved in imperial politics at all – came under suspicion solely because of their national origin. War hysteria and xenophobia were on the rise, fueled by reports of events at the front, enemy atrocities, and fears of spies or sabotage. In addition, the mood in society forced the authorities to react, so there were even outbreaks of anti-German and anti-Austro-Hungarian riots and acts of vandalism in the cities of the British Empire, which increased the pressure. In this tense atmosphere, the government required tens of thousands of hostile residents to register with authorities, carry identification documents, and report regularly to the local police. The Government stated that it would only intern those who posed a threat, but in practice, many of those arrested had no proven disloyalty and even had British citizenship (Luciuk, 2006, p.50). Ironically, despite this, hundreds of Canadians of Ukrainian descent volunteered to serve in the Canadian army during World War I, valiantly defending and helping their new homeland both in the rear and at the front (“Ukrainians served Canada in WWI, but many were also sent to camps”, 2022).

Canada’s First Internment Camps: Scope and Locations

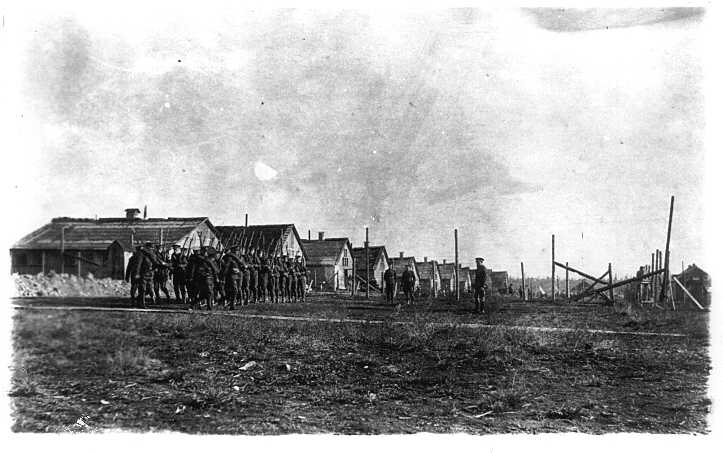

After the adoption of the War Measures Act, Canada quickly began to create internment centres, in other words, concentration camps. Between 1914 and 1920, a total of 8,579 “enemy aliens” were interned in Canada in 24 specified centers and camps stretching from Nova Scotia to British Columbia (Morin-Pelletier, 2022). Most of the internees were of Austro-Hungarian origin – about 5,000 of them were Ukrainians, alongside a smaller number of other Eastern Europeans (including Croats, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, Romanians, and Jews from the Austro-Hungarian Empire). The Canadians also interned several hundred German citizens, some Ottoman people (ethnic Turks), and Bulgarians. The network was not even limited to ethnic origin: among the internees were the homeless and unemployed, conscientious objectors, and members of outlawed political groups (such as socialists and trade unionists) who had no ties to enemy regimes but were considered subversive (Baird, 2022).

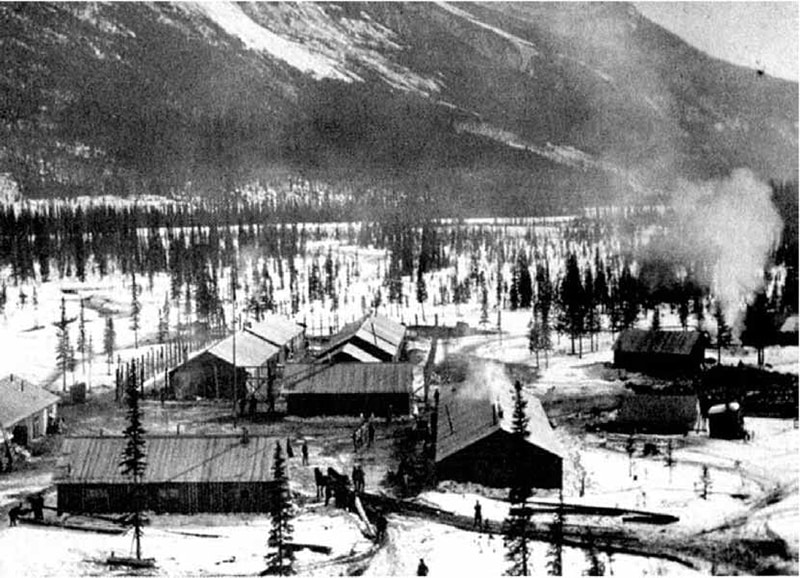

The internment camps themselves were scattered over a large distance. Some were set up in or near cities by converting existing facilities – for example, temporary detention facilities in Halifax and Montreal, or the famous case of a makeshift camp at Fort Henry Fortress in Kingston, Ontario (Kordan & Melnycky, 1991, pp.15-16). But most of the camps were set up in remote areas with extremely harsh climates, reflecting both security concerns and a desire to use prisoner labor in isolated areas. There were camps in the mountains and wilderness, such as those in the mountains of Alberta, on Spirit Lake deep in the forests of northern Quebec, in Kapuskasing, Ontario, and even at an iron factory in Amherst, Nova Scotia.

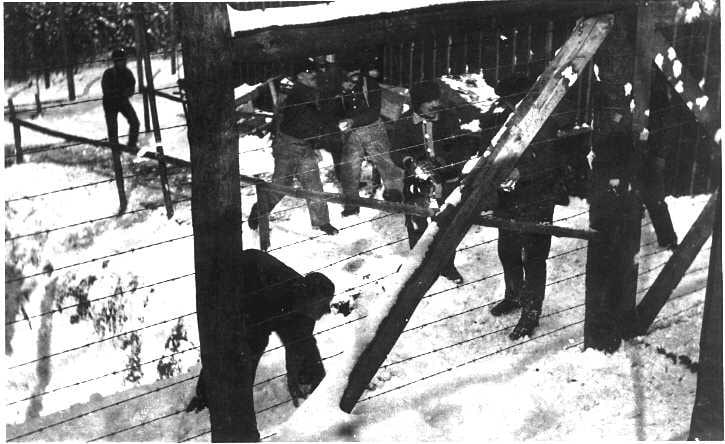

During the war, internment operations were carried out in a total of twenty-four camps, and only two camps – Spirit Lake, Quebec, and Vernon, British Columbia – were intended to place families, since women and children were officially released from internment. Despite this, 81 women and 156 children found themselves suffering behind barbed wire, voluntarily joining their husbands or fathers in order not to destroy the family (Morin-Pelletier, 2022). Life in these camps was Spartan; people lived in tents and barracks that were not equipped for the cold and were strictly controlled, like in a full-fledged prison.

Conditions in the Camps

For the internees, most of whom were young Ukrainian immigrant men, daily life in the camps was monotonous, difficult, and accompanied by constant instructions and supervision from guards. The Canadian government quickly realized that it could attract these “enemy aliens” to work on government projects, in particular in the construction sector, especially given the shortage of labor during the war. A striking example was the use of imprisoned Ukrainians for the development of Canada’s national parks. During the war, as budgets were cut, and Parks Commissioner James B. Harkin was given permission to use internees to improve parks in the Rocky Mountains (“First World War Internment Exhibit – Cave and Basin National Historic Site”, 2024). Internment camps were set up in Alberta and British Columbia national parks like Banff, Jasper, Mount Revelstoke, and Yoho to use prisoner labor. For example, men from the Castle Mountain Camp in Banff spent days clearing forests, building roads, and arranging amenities to make mountain parks more accessible (Farris, n.d.). One of the famous and large–scale projects was the road to Lake Louise, which was later popular among tourists, an iconic route in the Rocky Mountains, laid by Ukrainian internees in 1915-16 (Melnycky, 1998). The prisoners also worked on railway lines, laid the foundation for future infrastructure, extracted minerals, cut down forests, and drained swampy lands for agricultural development. Conditions in the camps varied from place to place, but many were described as harsh and even brutal. At Castle Mountain Camp in Banff, reports of mistreatment by guards circulated-beatings or punishments for minor violations were not uncommon.

The internees lived in overcrowded barracks, facing cold, hunger, and inadequate medical care, given the Spanish flu pandemic in those years (“The Spanish Flu in Canada (1918–1920) [National Historic Event]”, 2024). According to official data, 109 “prisoners” died in captivity from various causes – illnesses, work injuries, or hypothermia. At least six were shot while trying to escape. Many others had mental breakdowns or committed suicide, unable to withstand the uncertainty and humiliation of imprisonment (“Banff Internment Camp – Prisoner Suicide”, 1916). By 1916, as the war dragged on and the allocation of resources had to be changed, Canada faced labor shortages on farms and mines (Swyripa & Thompson, 1983, p.14). The Government decided that it would be more useful to transfer many internees “on parole” to private employers as cheap labor rather than keeping them in camps. Since the end of 1916, hundreds of Ukrainian internees were released to work on farms, in mines, and in railroad crews – still under supervision (Minenko, 1991, pp. 297-298).

Closing the Camps and Consequences

Although the First World War ended in November 1918 and Canadian soldiers returned home, freedom did not come to the internees immediately. It wasn’t until June 1920 that the last internment camp in Kapuskasing, Ontario, was finally closed, and the remaining prisoners were released (Kordan & Mahovsky, 2004, pp. 27-41). In total, more than 8,500 people were interned during Canada’s first national internment program. In addition, about 80,000 “enemy aliens” (mostly Ukrainians) were forced to suffer and regularly report to the police and carry special identification documents during the war (“New stamp draws attention to history of civilian internment in Canada”, 2025).

For the Canadian community of Ukrainians, in particular, the era of internment had long-term consequences. Many Ukrainian immigrants felt a deep sense of betrayal from the Canadian government, a government they had hoped would offer them a new life — but instead branded them as potential enemies (“Internment of Ukrainians in Canada, 1914–1920”, 2007). After their release, some internees felt such shame or fear of further persecution that they changed their names to sound less Ukrainian and more “Canadian”. Social pride and cultural expression among Ukrainian Canadians were significantly suppressed; some Ukrainian Canadians hid aspects of their heritage, fearing that they would again be called “non-Canadians” because of their origin (Luciuk, 1988). A huge psychological burden poisoned the lives of former prisoners for a very long time, and feeling extremely humiliated, people resorted to suicide even after years (Melnycky, 1998). At the same time, such stories about the psychological consequences remained largely untold for decades, as survivors and their families often tried to forget this painful period. For many years, Canadian history textbooks barely mentioned the internment of Ukrainians and other Europeans during the First World War. This entire episode was overshadowed by later events, most notably the much more widely publicized internment of Japanese-born Canadians during World War II, who eventually received an official apology and compensation (Gilmar, 2023). It wasn’t until the 1970s and 1980s that historians and activists began to unearth the layers of this forgotten history of the 1910s.

Recognition and Conclusion

Since the 1980s, the Ukrainian-Canadian community launched a campaign to officially recognize the injustice and compensate for the damage caused by internment during the First World War (Kordan & Mahovsky, 2004, pp. 45-62). These massive efforts led to memorial plaques being erected on the sites of former camps – by 2001, about two dozen plaques marking the locations of internment camps had been unveiled across Canada, from Banff to Halifax (Schmidt, 2013). These plaques, often funded from private sources or at the initiative of local communities, were the first visible reminders of a chapter of history that had long been ignored in official sources. The desire for official recognition bore fruit in 2005, when the Canadian Parliament unanimously adopted Bill C-331, the Law on the Recognition of the Internment of Persons of Ukrainian Origin (“Bill C-331 (Historical)”, 2005). This act recognized that people of Ukrainian origin were unjustly interned in Canada during World War I, and called for measures to perpetuate memory. Although this act did not include an official apology, it became an important symbolic milestone – the Canadian state finally recognized that what happened to the Ukrainian Canadians was a serious violation. It is important to note that after this act, the government entered into negotiations with Ukrainian Canadian organizations on specific compensation for damage. In 2008, an agreement was reached to establish the $10 million Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund, a charitable foundation created to support memorial and educational projects about internees throughout the country (“About the Canadian World War I Internment Legacy”, n.d.). Provincial governments and federal cultural heritage agencies have also contributed by preserving monuments and supporting educational initiatives. In the case of the Ukrainian Canadians, the community’s persistence ensured that their story would not remain a secret. These commemorations serve not only to honor the memory of the victims and their descendants, but also to educate all Canadians about the fragility of civil liberties in times of fear. This tells us how easily panic and prejudice in wartime can lead to disruption, discrimination, and suffering for thousands of people. At the same time, this story demonstrated the resilience of Ukrainian Canadians who built a new life and eventually won recognition for this injustice.

REFERENCES

About the Canadian World War I Internment Legacy. (n.d.). Internment Legacy Fund. Retrieved from https://www.internmentcanada.ca/about-us/

Baird, C. (2022, March 8). Canada’s Internment Camps. Canadian History Ehx. Retrieved from https://canadaehx.com/2022/03/08/canadas-internment-camps/

Banff Internment Camp – Prisoner Suicide. (1916, December 30). Crag & Canyon. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20101121214318/http://www.canadiangreatwarproject.com/transcripts/transcriptDisplay.asp?Type=N&transNo=783

Bill C-331 (Historical). (2005). Parliament of Canada. Retrieved from https://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-20.8/page-1.html

Ph.: Cherkasʹka, H. (2020, June 8). Навіть у Канаді українцям теж довелося пройти через концтабори [Even in Canada, Ukrainians also had to go through concentration camps]. Za Lashtunkamy. Retrieved August 6, 2025, from https://zl-ua.news/navit-u‑kanadi‑ukraintsiam‑tezh‑dovelosia‑proyty‑cherez‑kontstabory/

Ph.: Danileyko, O. (2023, October 6). A monument to interned Ukrainians unveiled in Canada [Article in Ukrainian]. Rayon.In.UA. Retrieved from https://history.rayon.in.ua/news/639151‑u‑kanadi‑vidkrili‑pamyatnik‑internovanim‑ukraintsyam

Farris, A. (n.d.). Canadian Dream to a Canadian Nightmare. OnThisSpot. Retrieved from https://onthisspot.ca/cities/banff/caveandbasin

First World War Internment Exhibit – Cave and Basin National Historic Site. (2024, April 8). Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://parks.canada.ca/lhn-nhs/ab/caveandbasin/culture/internement-internment

Gilmar, P. (2023, September 20). Saying sorry to Japanese Canadians. Legion. Retrieved from https://legionmagazine.com/saying-sorry-to-japanese-canadians/

Internment of Ukrainians in Canada, 1914–1920. (2007). Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association. InfoUkes. Retrieved from http://www.infoukes.com/history/internment/

Kordan, B. (2002). Enemy Aliens, Prisoners of War: Internment in Canada During the Great War. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/enemyalienspriso0000kord

Kordan, B. & Mahovsky, C. (2004). A Bare and Impolitic Right: Internment and Ukrainian-Canadian Redress. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Kordan, B. & Melnycky, P. (Eds.). (1991). In the Shadow of the Rockies: Diary of the Castle Mountain Internment Camp 1915-1917. CIUS Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.ca/books?hl=ru&lr=&id=0H-PMNunqCwC&oi=fnd&pg=PA3&dq=In+the+Shadow+opthe+Rockies+Diary+offthe+Castle+Mountain+Internment+Camp&ots=mEBER7DE7W&sig=i-wZxrOA-rpO1VNBlIOxEy9LQ-4&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=In%20the%20Shadow%20opthe%20Rockies%20Diary%20offthe%20Castle%20Mountain%20Internment%20Camp&f=false

Luciuk, L. Y. (1988). A time for atonement: Canada’s first national internment operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914-1920. Kingston, Ont.: Limestone Press. Retrieved from http://www.infoukes.com/history/internment/booklet01/

Luciuk, L. (2006). Without Just Cause: Canada’s First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914–1920. Kingston: Kashtan Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/withoutjustcause0000luci

Martynowych, O. T. (1991). Ukrainians in Canada: The formative period, 1891-1924. CIUS Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.ca/books?hl=ru&lr=&id=71Wnflm9lYgC&oi=fnd&pg=PR11&dq=Between+1891+and+the+outbreak+of+the+First+World+War,+some+170,000+Ukrainian+immigrants+arrived+in+Canada&ots=aXaB4ewPbo&sig=Gk7IMGI8D7ItH_HLMO4LaxCMPhY&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Melnycky, P. (1998). Perchaluk, William (Wasyl Perchaliuk). In Dictionary of Canadian Biography (Vol. 14). University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved from https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/perchaluk_william_14E.html

Minenko, M. (1991). “Without Just Cause: Canada’s First National Internment Operations”. In Luciuk, Lubomyr; Hryniuk, Stella (eds.). Canada’s Ukrainians: Negotiating an Identity. University of Toronto Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/canadasukrainian0000unse/page/288/mode/2up

Morin-Pelletier, M. (2022, June 27). Unearthing Canada’s First World War Internment History. Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved from https://www.historymuseum.ca/blog/unearthing-canadas-first-world-war-internment-history

New stamp draws attention to history of civilian internment in Canada. (2025, July 17). Canada Post. Retrieved from https://www.canadapost-postescanada.ca/blogs/personal/perspectives/internment-stamp-2025/

Parks Canada unveils a new exhibit recognizing Canada’s history of First World War internment in Yoho National Park. (2019, June 22). Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/parks-canada/news/2019/06/parks-canada-unveils-new-exhibit-recognizing-canadas-first-national-internment-operations-in-yoho-national-park.html

Schmidt, C. (2013, September 13). First World War exhibit opens in Banff National Park. CTV News. Retrieved from https://www.ctvnews.ca/calgary/article/first-world-war-exhibit-opens-in-banff-national-park/

Smith, D. (2013, July 25). War Measures Act. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/war-measures-act

Swyripa, F. & Thompson, J. (1983). Loyalties in Conflict: Ukrainians in Canada During the Great War. Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/loyaltiesinconfl00swyr

The Spanish Flu in Canada (1918–1920) [National Historic Event]. (2024, July 4). Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://parks.canada.ca/culture/designation/evenement-event/grippe-espagnole-spanish-flu

Ukrainians served Canada in WWI, but many were also sent to camps. (2022, November 8). Rotary Ladner. Retrieved from https://rotary-ladner.org/stories/ukrainians-served-canada-in-wwi-but-many-were-also-sent-to-camps#:~:text=Among%20the%20600%2C000%20who%20served,and%20those%20of%20Ukrainian%20heritage.

War Measures Act. (1914). LERM (Law and Electronic Resources Museum). Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20180913150558/https://www.lermuseum.org/index.php/war-measures-act