Written by SUSK Canada Summer Job Intern – Daniil Zhelezniak (Saint Mary’s University)

Cossack songs occupy a special place in Ukrainian culture, reflecting the courage, self-sacrifice, and spirit of the Zaporizhian Cossacks fighting for Ukrainian statehood. These folk melodies, whether they be rousing marches or soulful ballads, have been passed down from generation to generation, including in the Ukrainian community of Canada. Below are ten iconic Cossack songs (with their names in English and Ukrainian), as well as a brief overview of their historical context and the key text that conveys the spirit of each song.

The first on this list is the Instrumental folk March, embodying the valor of the Zaporizhian army, the “Zaporizhian March” was preserved and revived in the middle of the 20th century by the blind bandurist Eugene Adamtsevych (Bobrykova, 2003). His thunderous melody, often performed accompanied by traditional Ukrainian instruments such as the bandura, became extremely popular after conductor Viktor Gutsal arranged it in the 1960s. Today, this march is one of the most famous patriotic melodies of Ukraine, performed both at cultural events and at official ceremonies as a symbol of statehood and Cossack glory. Even without words, the music itself speaks of pride; one can almost imagine Cossack horsemen galloping across the steppe to battle, defending the borders of their homeland.

Despite the fact that this song was written in the 19th century by poet Yakiv Shchoholiv, it is stylized as a Cossack folk ballad (Sheveleva, 2024). It tells the touching story of a Cossack veteran who lost everything in the war – his faithful horse, weapons, and even his beloved. “The Turks killed a horse in a fall, the Poles stabbed a saber, and my dear girl disowned me”, he laments. Now, plowing the desolate steppe at will, the Cossack invites the wind and the forest to join him for dinner, but in response, there is only silence. The key part reflects his sadness: “Hey, those who are in the field… those who are in the forest… Come have dinner with me around the campfire…” – and yet the echo freezes in an empty meadow, and “the little pot cools down in the morning,” symbolizing his loneliness. Despite its sadness, the song celebrates the steadfastness of the Cossack spirit in the face of accumulating difficulties.

Also known as “The Song of the Cossack Nechai,” this historical ballad dates back to the 17th century and tells the story of the dramatic death of Bratslav Colonel Danylo Nechai during the famous Khmelnytsky uprising against the Polish crown (Shevtsova, 2019). It is included in the list of UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage that needs immediate protection. According to the legend (and the song), Nechai was warned about a Polish ambush, but out of pride and carelessness, he refused to escape, deciding instead to feast with a relative. The surprise attack took place without guards; Nechai and his men fought bravely but were outnumbered. The verses of the song tell how Nechai was killed and buried by his grieving comrades, who planted a red viburnum (kalyna) on his grave “so that his glory would be remembered throughout Ukraine”. This vivid image of Kalyna on the Cossack’s grave not only mourns the hero but also symbolizes the eternal memory of his glory and the heroes of Ukraine in general in folklore (Kovalchuk, 2025).

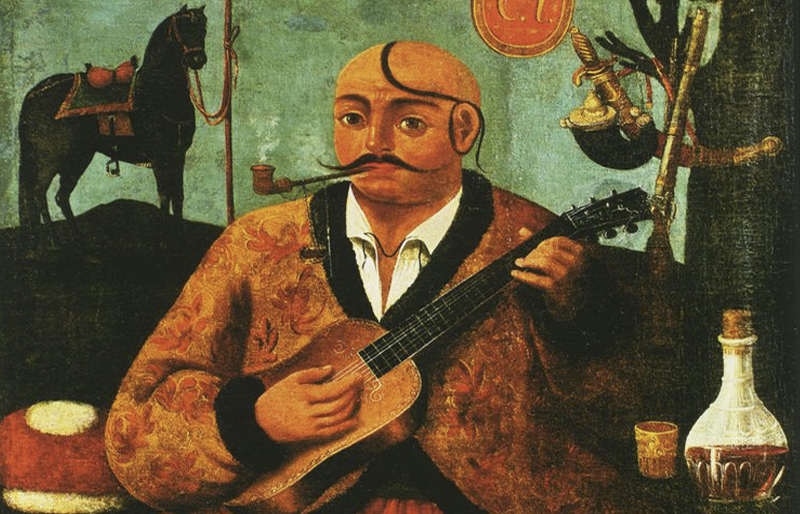

A lively Cossack marching song from the end of the 17th century. This folk tune glorifies the Zaporozhian army by creating a scene in which soldiers march under a hill where peasants harvest wheat. It is known that the names of two legendary Cossack leaders are mentioned in it: “Doroshenko is ahead…”- “Doroshenko is riding ahead, leading his glorious Zaporozhian army”, followed by a playful nod towards Petro Sahaidachny (Zakharchuk, 2023). One of the oft-quoted poems mocks Sagaidachny, who recklessly ”traded his wife for tobacco and a pipe”, emphasizing that he preferred the life of a Cossack to a family one. In the song, fellow Cossacks also call out to him: “Hey, Petro Sahaidachny, come back, take your wife and give me the phone!”. This good-natured exchange of views highlights the Cossacks’ dedication to freedom and military duty, which they celebrate even at the expense of personal ties.

First popularized in the middle of the 18th century (the author of the text is Semen Klymovsky), this romance has become one of the most beloved Ukrainian folk songs (Bazhan, Zasenko, Kryzhanivskyi, Malyshko, Nahnibida, & Novychenko, 1956, p.319). It tells about the tender farewell of a young Cossack to his beloved when he goes on a long, distant, and risky campaign. The opening line remains iconic: “A Cossack rode across the Danube, saying: “Farewell, my girl”; to which he receives an answer from her – “Wait, wait, my Cossack, your girlfriend is crying, just think about who you’re leaving behind.” Similar situations can be massively found in the modern realities of the war with Russia, where the military leaves their loved ones and very often forever. This bittersweet song with its melancholic and at the same time gentle melody won the hearts not only in Ukraine, but throughout Europe. It inspired many European composers and even found a new life in Germany in the form of an adapted song “Schöne Minka”, spreading the fame of the Cossack’s farewell beyond the borders of Ukraine (Clements, 2007). The key refrain, in which the Cossack comforts his crying love and promises to return, embodies the romantic spirit and national soul of Ukraine: even in parting, there is hope and loyalty.

An incendiary folk song of camaraderie arose, “Unhitch, lads, horses” in the 19th century, and later was popularized by choirs in the 20th (Repetun, 2022). It features a group of Cossack horsemen setting up camp after a long ride, and even has a flirty subtitle. The famous opening line begins with the words: “Unhitch the horses, boys, and go to rest, and I’ll go to the green garden to dig a well,” followed by a beautiful and famous chorus about Marusya. The plot is such that when one Cossack sneaks to the well in the garden to meet a girl, he sings to her and offers her a ring, but discovers that she resents him for chatting with another night. Despite the carefree romantic tone, the lively tempo of the song and the energetic choruses made her a favorite at Cossack gatherings. This song highlights the joyful, human side of the life of the Cossack warriors, who in peaceful moments laughed, cared for their loved ones, and had fun under the night sky, which may also have a reality with modernity.

The incendiary Polish-Ukrainian folk song of the 19th century, “Hey, falcons!” or “Hej, sokoły” (in Polish), enjoys great popularity among Ukrainian communities due to its theme of homesickness (Kharchyshyn, 2019). This song, which is often sung in Ukrainian or Polish (or a mixture of the two), depicts a Cossack saying goodbye to distant Ukraine. Falcons are a symbol of the fact that they are fast messengers of love and memory. The thrilling chorus is addressed directly to them: “Hey, falcons! Remember the mountains, the foxes, the distance!– “Hey, falcons! Fly past mountains, forests, and valleys!” – taking the hero’s heart back to his beloved and native land with typical landscapes. It is believed that poet-composer Tomasz Padura wrote the song around the mid-1800s (Balandina, & Bolotnikova, 2020). This song combines a rousing melody with thoughtful words about homesickness and courage. His enduring popularity (which has been revived even during recent events) shows how strongly he resonates with everyone who has ever been far from home, but keeps his homeland in his heart. “Hey, Falcons” remains the all-Ukrainian anthem of love for Ukraine and the Cossack spirit of freedom.

This solemn Cossack folk song paints the image of a suddenly blooming dry oak tree – a metaphor symbolizing the rallying of forces in a difficult moment. Originating in the early 18th century, it accompanies the scene of Cossacks preparing to go to war to defend their homeland (G. J., n.d.). The lyrics of the song begin with the call: “Oh, develop, you dry oak, tomorrow there will be frost…”Oh, bloom, you dry oak, because tomorrow there will be frosts,” as if calling for perseverance before the impending storm. In one particularly expressive verse, a young Cossack says goodbye to us: “Goodbye, father, goodbye, motherland, goodbye, Beautiful! If I go to the market, I may die there” – “Goodbye, father, goodbye, mother, goodbye, Ukraine! Because I’m going to war–maybe I’ll die there.” In the final chorus, the song blesses the Cossack brotherhood: “May the Cossack family never perish in this world!” This key text, often sung in full voice, embodies the spirit of patriotic pride and faith in the resilience of the Cossack people even in the most difficult times.

The popular folk song of the Cossack era of the 17th century reflects the tragic and heroic struggle of Ukraine against foreign invaders (Tatars, Poles, Turks and Muscovites) (““Homin, homin po dibrovi” analysis”, 2023). The action of the song unfolds as a dialogue between a Cossack mother and her son. In anger and fear, the mother tells her son to leave and mocks the fact that every enemy – “horde” (Tatar horde), “Lyakh” (Pole), “Turchin” (Turk), “Moskal” (Russian) – could just as well capture him. The young Cossack defiantly replies that all these enemies “know him”: the Tatars avoid him in the open field, the Poles treat him with beer and mead, the Turks reward him with silver and gold, and the Moscow tsar tries to win him over. In the end, he leaves to fight the common Tatar-Turkish threat. In the end, in a heartbreaking outburst, the mother calls: “Come home, son, I’ll wash your hair!” But the Cossack’s voice echoes back from afar: “Mom, the rains will wash me, the wild winds will dry me.” These texts emphasize both the unshakeable independence of the Cossack and the tragedy of the family affected by the war. This remains a powerful reminder of the sacrifices made by Ukraine in the struggle for freedom and statehood.

Concluding on a jubilant note, this invigorating drinking song, popular to this day and often present even in modern cinematography in Ukraine, invites listeners to enjoy life even in troubled times. The song “Hey, pour the wine,” which probably appeared on the Cossack outskirts and is sung in Sich inns, calls on comrades to raise a toast to good luck. The first poem is a classic Ukrainian toast: “Hey, fill the glasses, so they overflow, so that our fate does not leave us, so that life in this world will be better!”. The song calls on everyone to put aside their sadness: “Destroy our troubles, and everything will become more fun. Let’s drink to happiness, let’s drink to fate, let’s drink to everyone who is dear to us!” Let’s drink to every rousing chorus, brothers!”. It is both a celebration of camaraderie and an audacious proclamation that adversity will not break the Cossack spirit. To this day, when Ukrainians sing clinking glasses with vodka or wine, it sounds like a cultural memory of Cossack feasts. In other words, it demonstrates the sincere optimism of the people.

REFERENCES

Balandina, N., & Bolotnikova, A. (2020). Polish-Ukrainian song “Hej, sokoły!” (“Hey, Eagles!”) as an intercultural communicative phenomenon: Польсько-українська пісня «Hej, sokoły!» як інтеркультурне комунікативне явище. Przegląd Wschodnioeuropejski, 11(1), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.31648/pw.5983

Bazhan, M. P., Zasenko, O. Ye., Kryzhanivskyi, S. A., Malyshko, A. S., Nahnibida, M. L., & Novychenko, L. M. (Eds.). (1956). Songs and romances of Ukrainian poets (Vol. 2). Kyiv: Radianskyi Pysmennyk. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/nudha01/page/n321/mode/2up?view=theater

Bobrykova, T. (2003, May 1). “Про Мого Батька, Бандуриста України” [About my father, bandurist of Ukraine]. Crimean chamber (Krymska Svitlytsia) (in Ukrainian). Retrieved from http://svitlytsia.crimea.ua/index.php?section=article&artID=838

Clements, G. R. (2007). Situating Schubert: Early nineteenth-century flute culture and the “Trockne Blumen” variations, D. 802. State University of New York at Buffalo. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/openview/4cb64b68cb8a018ee0eb658b62b525ba/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

- J. (Jay J.). (n.d.). “Rozvyvaysya ty, vysokyy dube…” analysis (literary profile) [«Розвивайся ти, високий дубе…» аналіз (літературний паспорт)]. Dovidka.biz.ua. Retrieved from https://dovidka.biz.ua/rozvivaysya-ti-visokiy-dube-analiz/

“Homin, homin po dibrovi” analysis [«Гомін, гомін по діброві» аналіз]. (2023, October 9). Vkorzinu. Retrieved from https://vkorzinu.com.ua/literatura-ta-istorija/gomin-gomin-po-dibrovi-analiz.html

Kharchyshyn, O. (2019). “Hej, sokoły!” (“Гей соколи!”): тексти і контексти пісні”. The Ethnology Notebooks.Retrieved from https://nz.lviv.ua/archiv/2019-5/22.pdf

Kovalchuk, O. (2025, January 7). Калина – символ України: історія, значення та традиції [Kalyna – the symbol of Ukraine: History, meaning, and traditions]. Topiclab. Retrieved from https://topiclab.com.ua/kalyna-symvol-ukrayiny-istoriya-znachennya-ta-tradycziyi/

Repetun, S. (2022, August 15). History of the song “Rozpryahayte, khloptsi, koni” [Історія пісні «Розпрягайте, хлопці, коні»]. Історії українських пісень та світових хітів. Retrieved from https://songs.in.ua/rozpryahayte-khloptsi-koni/

Sheveleva, M. (2024, November 5). Yakiv Shhoholiv – the last Ukrainian romantic. Ukrainian Interest (Український інтерес). Retrieved from https://uain.press/blogs/yakiv-shhogoliv-ostannij-ukrayinskij-romantik-1105078

Shevtsova, A. (2019, January 14). Козацькі пісні: Символ гордості Дніпропетровщини [Cossack songs: The symbol of pride of the Dnipropetrovsk region]. Dnipro Library. Retrieved from https://www.dnipro.libr.dp.ua/Kozacki_pisni_folklor_tradicii

Zakharchuk, Y. (2023, September 16). Ukrainian folk songs that everyone should know. Ukrainian in Poland. Retrieved from https://www.ukrainianinpoland.pl/uk/ukrainian-folk-songs-that-everyone-should-know-uk/